The Context

At the very outset, I would like to share that I am not a trained historian, but a theatre practitioner who is consistently looking at the processes of theatre production and consumption as a student during the late 1990s and continuing till date as a faculty member at the University of Delhi and a theatre practitioner with Atelier Theatre, New Delhi, working largely with young actors and a curator of a multi-city campus theatre festival, ACT (Atelier’s Campus Theatre) Festival since 2007. Moreover, the area I have attempted to “source my story” in this paper is very “new” along with the “new” archive, which has not been looked at. Therefore, the types of questions I would raise in the subsequent argument and the interpretations I will make may drastically differ from the historian’s perspective. This point will become evident as I go through this paper along with sharing a few reference pictures I have collected from the annual reports from the magazines of the colleges. Additionally, interviews with practitioners and the audience were also used to construct the nine-decade[1] history of theatre on the University of Delhi campus, beginning with the Shakespeare Society of St. Stephen’s College, University of Delhi.

Within the textual and performative traditions, a comprehensive broad-level database[2] is created and looked at. Photographs, brochures, blurbs, interviews, reviews, newspaper cuttings, and first-hand information from actors/directors/audience from the present to the earlier (as much as possible) is used to compare the contextual references and performance.

University Campus, as a space, has always been a hub of cultural activities, per se. The inherent diversity in this space, further, allows serious debates about the processes of cultural production and consumption. The kind of theatre practice which forms a part of this alternate theatre space since its inception; the politics of the “region” where it is produced and consumed; the role played by the students on the one hand and the movements on the other in shaping Campus Theatre are some of the concerns of this paper. Furthermore, I would also like to probe the question of “people” who identify and constitute this “region” and the timeframe of their existence here.

This paper attempts to map the history, changes, and continuities within the Campus Theatre spanning over a period of nearly nine decades within the backdrop of the cultural changes that were highly influential in the international, national, and regional contexts. The theoretical framework is based on the references given at the end. The first part attempts to explore in detail the beginning of theatre on the campus along with subsequent emergence of new theatre groups. The second part will attempt to display the relationship between the “archive” and the “story” that marks the characteristic shifts in the theatre on the campus.

Is this process of “identity formation” and its corresponding “representation” fixed?

Is this theatre essentially political?

What kinds of text does it undertake and what are the themes/contexts that it involves, and whom is it catering to?

Are there any theoretical models being employed to perform them (let us say Stanislavski etc.) as is done in institutional platforms like the National School of Drama?

These are a few questions the paper would like to address, thus problematising the inherent heterogeneity in the Campus Theatre traditions. In addition, the continuity of the urban campus tradition in the present context provides ample scope to look at the tradition within the context of time and space.

Part I: The Beginning of Theatre on Campus

Regions did not exist in airtight compartments, of course, and the circulation of goods, people and ideas throughout the subcontinent (region) and beyond was an important source of medieval India’s dynamism.

Talbot’s statement on the dynamism of medieval Indian society is not just a tangential remark to mention here, perceiving the university campus as a region. On the contrary, it becomes very pertinent vis-à-vis the Campus Theatre in the University of Delhi, which clearly demonstrates Talbot’s statement substantially. The theatre tradition emerging out of colleges as an alternate space is always contested, is in continuous flux, and is a counterpoint to the so-called professional theatre with or without ideological affiliation. Theatre on the campus has gained voice and is growing stronger with each academic year as an educative and communicative movement. With a countable group size of a few colleges till the late 1990s, Campus Theatre in the University of Delhi has picked up a momentum[3] that is unprecedented in the history of Campus Theatre Tradition.The study of these regional patterns of cultural practice, therefore, becomes very important to analyze the “emergence of distinctive local societies.” The region of Campus Theatre exhibits multiple dynamic propositions since its inception in general and particularly after the 1960s, including a level of physical and social mobility and a large degree of fluidity in the configuration of themes and idioms. In the era when urban societies in India were emerging substantially, many other spaces must have resembled this region. If this postulation is correct, then the region of Campus Theatre in the University of Delhi serves far better as a parameter to understand the validity of characterisations of other rapidly changing societies.

The distinct cultural features of this region exhibit a bunch of isoglosses, a specific type of language border provided by students coming from different states and creating a region, which we term here as Campus and the phenomenon occurring here as Campus Theatre.

Campus as a Cultural Region

The last quarter of the nineteenth century marks a radical shift in theatre practices in India, and that has remained central to social and political movements along with the strong Parsi Company Theatre at its zenith. It received a very significant impetus with the forum of progressive writers and political activists (IPTA) in the early second quarter of the twentieth century raising concerns in post-Independence India as well.

The formation of Sangeet Natak Akademi, India’s premier institute of music, dance and drama in May 1952 and the subsequent decision to create an independent drama institute (now known as NSD) by SNA “to meet the growing needs for developing a National Theatre in the country” bring together a set of questions with regard to the meaning of “naional” at that point of time on the one hand and the subsequent developments in “Modern Indian Theatre” on the other. Within this dramatic framework, the emergence of theatre on the University of Delhi campus from Shakespeare Society in 1920s to a handful in the late 1950s and early 1960s and later with the creation of ‘Jana Natya Manch’ in 1970s and Sapru House Shows during the same period and subsequent formation of independent theatre groups like Pierrot’s Troupe (1989), Asmita Theatre Group (1993), and Bahuroop Theatre (1996) and their engagement with Campus Theatre represent a wide spectrum of perspectives and reveal the multifaceted, hybrid and contested formations of modern Indian theatre.

The theatre movement on the University of Delhi campus took a significant move in the late 1960s with the formation of theatre groups in the various colleges: Miranda House, Kirori Mal College, Lady Sriram College and Ramjas thereby challenging the hegemony of exclusive Shakespeare plays by the Shakespeare Society at St. Stephen’s College adhering to the age-old myth of “a great tradition in theatre.” This shift has consolidated in a major manner in the 1990s with the Sriram College of Commerce, Khalsa, Hansraj, Venkateswara, Kamala Nehru, and Gargi College joining in with productions thematically responding to the times, addressing and contesting the notion of Indian Theatre or rather theatre practices in India.

The Jana Natya Manch was started in 1973 by a group of Delhi’s radical theatre amateurs, who sought to take theatre to the people. It was inspired by the spirit of the Indian People’s Theatre Association (IPTA). Its early plays, though initially designed for the proscenium, were performed on makeshift stages and chaupals in the big and small towns and villages of North India. It also experimented with street skits. Janam‘s street theatre journey began in October 1978.

The history of Campus Theatre on the campus of the University of Delhi dates back to 1924 with theatre productions of Shakespeare Society, producing Shakespeare plays in English and continues until the production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream in Hindi in 2007 by Shakespeare Sabha at St. Stephens College. From 1924 to 1959, until The Players, the theatre group of Kirori Mal College was initiated by late Frank Thakur Das, and by and large, the campus of the University of Delhi witnessed Shakespeare through the plays performed by the Shakespeare Society at St Stephen’s College.

Alongside emerged Anukriti, the Hindi theatre group at Miranda House in 1957, with Shail Kumari of the Hindi Department spearheading the Campus Theatre movement. Similarly, Lady Shriram College (LSR) began its theatre activity a few years later in the late 1960s. Theatre activities in Punjabi language are also recorded during the 1950s at SGTB Khalsa College. S.S. Uppal from the Punjabi department directed Balwant Gargi’s Dr. Palta and K.S. Duggal’s Deeva Bujh Gaya (The Lamp Is Doused) and Jutiya da Jora (A Pair of Shoes).

Subsequently in 1967, the founder principal of Gargi College, Indira Thakurdas, in the very first year, staged two plays titled Uljhan (Dilemma) and Dhong (The Sham), followed by Dadi Maa Jagi (The Waking up of the Grand Mother) and Qatal Ki Havas (The Lust of Murder) as public performances. Shakespeare Sabha also came into existence in 1978 at St. Stephen’s college with the intention of doing classics in Hindi.

The Collegiate Drama Society was formed in the year 1978 by C.D. Sidhu. Sidhu has produced about 50 original plays in English, Hindi, Punjabi and Urdu. The Pandies Theatre was started by Sanjay Kumar in the 1990s and consisted of largely adaptations and original scripts to generating awareness on diverse issues ranging from feminist theatre to gay rights, to child rights and to the rights of religious minorities.

A large number of active theatre groups of today were the ones that came into existence in the 1990s and constitute the present-day Campus Theatre along with the older ones. Some of the colleges have only Street Theatre groups involved and engaged in social themes, whereas the others have groups practicing both: Stage along with Street, and the themes are varied and not consistent. Recent developments vis-à-vis theatre in the commerce/business Colleges, including the Sri Ram College of Commerce, College of Business Studies, and Guru Gobind Singh College of Commerce, are a notable trend and asks for a meticulous study of the themes taken up by these Institutes. A few colleges also have two theatre groups creating plays in English and Hindi separately, like Lady Sri Ram College (LSR) and Miranda House.

With available information in the college magazines and annual reports, about 385 theatre productions in Hindi, English, Urdu, Hindustani, as well as bilingual ones extending over a period of 85 years, are recorded by the Shakespeare Society and The Players alone. Campus, therefore, as a region becomes very relevant with regard to the production and consumption of art and literature. Further, it becomes important to understand Campus with its multiple cultural identities. It would be better to look at the confluence of cultural identities from different regions constructing another region. It is a cultural region indicating patterns of human activity and the symbolic structures that give such activities significance and importance, thereby constructing an identity which is unique and changeable at the same time. A structure which could be “understood as systems of symbols and meanings that even their creators contest, that lack fixed boundaries, that are constantly in flux, and that interact and compete with one another.”

It is indeed pertinent to note that the fabric of Campus Theatre is the multiregionality of the actors coming from the noncosmopolitan regions with regional aesthetics and the transitory nature of Campus Theatre with different approaches and inclinations regarding ideology, text, and practice. The time frame of the students who join theatre groups on campus is mostly three years, and this flux of movement creates both rupture and continuity as these students graduate after the span of three years and move ahead. Conversely, the characteristics of the Campus Theatre are also in continuous flux—from romantic to experimental and radical.

If one has to examine the dynamics of theatre being performed on campus and to see what has gone into the construction of its historical and cultural formations, one can apparently conceive that the theatre tradition emerging out of the campus in an alternative space, which, like the transitory nature of the students on campus, is temporary on the one hand and is in a continuous state of flux, on the other. This ambivalent, yet vibrant status of rupture and continuity of the Campus Theatre tradition is remarkable vis-à-vis the mobility and freshness of students in every academic session. The continuities and discontinuities of students eventually lead to new sets of refreshing, revitalising, and rejuvenating dynamism within the tradition.

Is this kind of construction of theatre a counterpoint to the so-called professional theatre (both ideological and/or otherwise)—and could be the point of entry to understand this tradition, as a contrast to the dominant theatre traditions that we find outside the campus.

Part II: The Archive and the Story

Shift from Colonial to Desi

The following statement about the founding of the Shakespeare Society at St. Stephen’s College in the annual report of January 1925, page 27, by the then, President of the Society, H. Wilson Padley bears testimony to the approach of the theatre group to Shakespeare with its “threefold purposes”:

- To produce one Shakespearean play every year.

- To study Shakespearean drama when the Society is not engaged in producing a play.

- To keep April 23 as Shakespeare Day.

Immediately after the founding of the Shakespeare Society in 1924, approximately ten productions in Urdu and English appeared in this brief phase at St. Stephen’s College. The Urdu Dramatic Club was very active and popular among the college students, as the chronicles in The Stephanian reveal.

One witnesses two kinds of theatre practices simultaneously taking place at St. Stephen’s at this juncture of time. The emergence and influence of Urdu-Parsi theatre led to the production of popular plays on campus as well. In addition to the Founder’s Day Urdu drama, Agha Hashr Kashmiri’s Khubsurat Bala (The Beautiful Trouble, 1909), scenes from Shakespeare’s The Merchant of Venice were rehearsed and performed in 1925.

The campus of Delhi University has witnessed 73 productions of Shakespeare to date, and a majority of them are comedies with the effort to recreate the Elizabethan era. Most of the costumes looked like tailor-made versions taken from the help books. The emphasis was more on individual costumes and less on thematic design as one can register through the interpretation of the stage setting.

From the Comedy of Errors (1950), through the background curtains employed in A Midsummer Night’s Dream (1952), through the frills of the costumes in Much Ado About Nothing (1953), capped Hamlet with loose cuffs in Hamlet (1957) and through the make-up of the witches in Macbeth (1954) until the late 1970s, the Shakespeare Society adhered to the “threefold purposes,” rather religiously. After a long-decade-debate about St. Stephen’s “Great Tradition in Theatre,” deviations were seemingly allowed in the 1990s.

Macbeth of 1954 and 1995

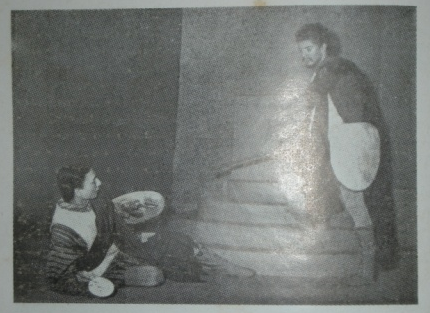

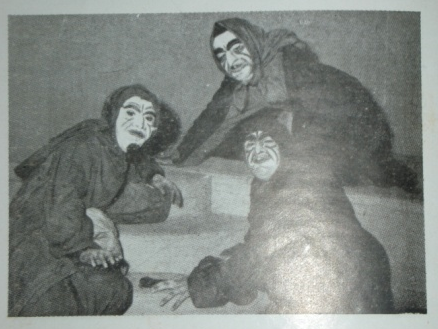

An interesting change in stagecraft in the 1995 production of William Shakespeare’s Macbeth by the Shakespeare Society is seen in the 1954 production of the same play (see Figures 1 and 2 below).

Figure 1. Macbeth (1954) by the Shakespeare Society, St. Stephen’s College

Vishwanathan Krishnan as Macbeth

Figure 2. Macbeth (1995) by the Shakespeare Society, St. Stephen’s College

The Macbeth of the 1990s is more symbolical and thematically indigenous than the Macbeth of the 1950s, though the language remains English. While 1990s production used sticks and lathis to represent the forest and with meticulous make-up on characters, the 1950s production relied heavily on masks. Make-up is an offshoot of realism, which is an expensive activity, and very few colleges and productions can afford this. C.D. Sidhu, who taught English Literature at Hansraj College and practised theatre on campus with the Collegiate Drama Society, elaborates this point in his interview taken for the study,

Realism reached colleges through the NSD students trained under Alkazi, who had directed plays at Miranda House, Indraprastha College, LSR and St. Stephens. Prior to that most of the student productions were very basic and raw with very few props and sets…

Moreover, the costumes of Macbeth, Lady Macbeth, and Ross in the picture clearly exhibit the shift in colonial approach, hitherto employed by the Shakespeare Society, to the newer interpretations. This, again, is a landmark as far as the tradition of theatre at St. Stephen’s is concerned. Shakespeare’s Othello was attempted for the first time in the history of the Shakespeare Society in 1998, only after 74 years of its inception. The reasons for not producing it earlier are not expressed, but it seems the challenge it gives to the actors was the reason behind it.

It was in 1970 that the Campus Theatre saw a major shift thematically. People like Ravindra Ray and Arvind Narayan Das from St. Stephen’s College directed perhaps its first street play called ‘India 69’, which was a parody of India’s closeness to the US. Moreover, the productions based on the plays by Oscar Wilde, Anton Chekhov, Rupert Brooke, Jean Cocteau, Ferenc Molnar, Jean Paul Sartre, P.L. Deshpande, Norman Holland, Jean Anouilh, Maxwell Anderson, William Saroyan, Joe Corrie, Lady Gregory, Arthur Koestler, and Maxwell Anderson as adaptations, translations, and originals in Hindi and English were also seen in the 1960s. The Players introduced and experimented with new European and Indian authors on the campus stage that continued in the subsequent years.

In the 1970s and 1980s, Campus Theatre witnessed a significant shift with the choice of plays. Playwrights including John Osborne, Arthur Miller, Vijay Tendulkar, Sharad Joshi, Tom Stoppard, Israel Horowitz, Mohan Rakesh, Woody Allen, Mahesh Elkunchwar, Eugene O’ Neill, and Howard Brenton were staged along with Lalit Sehgal, Sudhir C. Mathur, Lakshmi Narayan Lal, Ganesh Bagchi, and M.M. Bhasin until the 1990s. The change in the socio-political scenario across the globe and at the national/local level was apparently reflected in the choice and responses were also expressed.

Lalit Sehgal’s Hatya Ek Aakar ki was staged in 1971 by The Players. Written in the 1960s, this play deals with Gandhi’s ideas of ‘truth’ and ‘non-violence’ through rigorous historical scrutiny.

The inherent cultural complexities of the Campus Theatre provide a diachronic dimension with St. Stephen’s Shakespeare Society’s colonial negotiations on the one hand and the theatre groups appearing in the 1960s exploring their identity on the other along with the establishment of Sangeet Natak Akademi and National School of Drama. The choice of authors from 1920s to the subsequent decades elucidates a fairly substantial shift from colonial to desi and, of late, to self-scripted plays.

There was tremendous anxiety among the theatre workers at St. Stephen’s about the choice of themes as well, as also pointed out by Novy Kapadia, a student at St. Stephen’s College in the 1970s, in the interview taken for the study,

The three main people behind it were: Ranjana Ray, who acted in the Shakespeare Society but felt it was too class stratified and too traditional, supported by Dilip Simon, a very bright scholar who taught History at Ramjas and now doing some research work in Australia, and Arvind Narayan Das who went on to become the Deputy Editor in The Times of India. Ravindra Ray was a theatre man and was very active but the ideas were contributed by all three of them. This was St. Stephen’s first break where they moved away from conventions and radical theatre came into being. Newspapers like The Statesman and some magazines reported that there was a radical group challenging the might of the state. This whole idea of using popular culture went really well with the audience.

After the unsuccessful production of The Winter’s Tale, and as reviewed by Shomit Mitter, a final-year MA student of English in the 1981 centenary year annual issue of The Stephanian, Amarjeet Sinha, a III-year History (Hons.) student of St. Stephen’s in his essay, The Shakespeare Society: A Plea for Reorientation responds:

Tradition, they say, is a distinct component of St. Stephen’s College. To be traditional is to serve the college best. We beg to differ, at least in our conception of being traditional. It does not imply a moratorium on thinking, on change. One has to appreciate the times. If Shakespeare is brilliant, it is not a sanction for imposing him annually. Let us give Tennessee Williams, or Bertolt Brecht, or any like him, a chance. That is a plea.

The 1970s marked the beginning of serious meaningful theatre activities on the University of Delhi campus in more ways than one. The number of productions increased tremendously along with the varied choice of scripts. Alongside, the Shakespeare Society also started to dabble with non-Shakespearean plays in a big way and Tom Stoppard’s Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead was the most successful play in 1979.

Needless to say, this was the golden age of theatre in India with playwrights like Vijay Tendulkar, Mohan Rakesh, Adya Rangacharya, Badal Sircar, Girish Karnad, and actors including Om Shivpuri, Naseeruddin Shah, Manohar Singh, Uttara Baokar, Jyoti Subhash, Om Puri, Subhash Joshi, B. Jayashree, Jaydev, and Rohini Hattangdi with directors like Ebrahim Alkazi, and B.V. Karanth. The trend of the theatre movement outside also reached the campus with many groups managing regular full-length productions along with in-house one-act plays for Inter-college competitions.

With varied themes in the 1980s that touched upon the then contemporary sociopolitical realities of the local and the global, Campus Theatre represented almost every issue from nuclear weapons to immigration and the politics of the play; every playwright from Brecht and Sharad Joshi to Tendulkar and Pinter; genres from realistic to political and classic (Shakespeare Sabha Shakuntalam in 1988).

Evidently, the angst of 1970s and 80s with regard to theme and language continues till date and the choice of the style of language becomes very important to sustain the theatre group, not only in the professional arena but in college groups as well. The Shakespeare Sabha had to struggle against the same hegemonic stand for quite some time with regard to sponsors and supporters, which the Shakespeare Society could easily negotiate.

When all forms of decolonisation had made their presence felt, St. Stephen’s College for a long time tried to resolutely resist any form of decolonisation from making its influence felt within the campus and the Shakespeare Society’s insistence on doing one Shakespeare play as its annual production perhaps is a reflection of this recalcitrant kind of approach towards culture. Fortunately, this single-minded orientation of the Shakespeare Society ceased to exist later, though the annual Shakespeare production still continues to be a part of their tradition.

Playwrights like Girish Karnad, Bhisham Sahni, Vishnu Prabhakar, Ionesco, Dario Fo, Franca Rame, and Swadesh Deepak joined in the strong corpus of the 1980s, which continued into the 90s as well. Howard Brenton, Badal Sircar, Sharad Joshi, Safdar Hashmi along with Shakespeare, Kalidasa, and Sudraka. Jan Ruppe and Nina Rapi were also staged in English in this decade.

Tendulkar was staged by both the theatre groups, while Sudraka and Shakespeare (tragedies mostly) were exclusively produced by Shakespeare Society in Hindi and English, respectively. Re-creation of Greek mythologies were also staged: Medea by Franca Rame. And an adaptation of Ionesco’s The Lesson also formed a part of the corpus.

The Visible Shifts

The language of Campus Theatre has also seen radical shifts from the colonial in the 1920s to bilingual in the 1970s and of late to the multilingual. Quite clearly, the study of Campus Theatre in the University of Delhi campus demonstrates the following shifts:

- from the colonial to local sensibilities in terms of author, themes, stagecraft and audience;

- from monolingual to multilingual and incorporation of dialect varieties;

- from the cosmopolitan to the vernacular elements;

- from conventional theatre to experimental theatre;

- from a uni-centred activity to a multi-centred but collaborative activity; and

- from realistic to expressionistic to multimedial stagecraft.

With regard to the responses to various issues, Campus Theatre can be possibly viewed from three different dimensions:

- A spatial dimension incorporating global, national, and local categories.

- A temporal dimension involving three phases—pre-1970s, post-1970s, and from 1990s till date, keeping the then existing socio-political movements/changes in view along with the cultural negotiations and subsequent choice of language, script, theme, genre, visual, music, and adaptation.

- Third, ideological dimensions of movements that influenced campus theatre such as student unrests, feminist movement, Mandal Commission agitation, Hindutva issue, globalisation, etc. provided the background.

It would be interesting to see the course of action of the Campus Theatre from this stage onwards with the coming of state-of-the-art technology on the one hand and the struggle to continue the tradition in the marginalised space on the other.

Appendix I

This table provides the details of the plays produced on the campus of the University of Delhi in terms of the year of production, name of the play, the author the name of the group that produced the play, and the language of the play. Spaces left blank suggests the nonavailability of information. Question marks are placed against the names of theatre productions on account of ambiguity. ’Shakesoc’ indicates Shakespeare Society and ‘Shakesabha’ indicates Shakespeare Sabha.

| Year | Text | Author | Society | Language | Original/ Adaptation |

| 1924 | Julius Caesar | Shakespeare | Shacksoc | English | |

| Khubsurat Bala | Agha Hashr Kashmiri | Urdu Dramatic Club | Urdu | ||

| 1925 | A Winter’s Tale | Shakespeare | Shakesoc | English | |

| 1926 | Antony and Cleopatra | Shakespeare | Shakesoc | English | |

| 1927 | – | – | – | – | |

| 1928 | Twelfth Night | Shakespeare | Shakesoc | English | |

| 1929 | Macbeth | Shakespeare | Shakesoc | English | |

| 1930 | Much Ado About Nothing | Shakespeare | Shakesoc | English | |

| Ghalat Fahmi | – | Urdu Dramatic Club | Urdu | ||

| 1931 | Richard II | Shakespeare | Shakesoc | English | |

| 1932 | The Merchant of Venice | Shakespeare | Shakesoc | English | |

| 1933 | Hamlet | Shakespeare | Shakesoc | English | |

| 1934 | One Act Play | – | Shakesoc | English | |

| 1935 | Henry IV Part I | Shakespeare | Shakesoc | English | |

| 1936 | – | – | – | – | |

| 1937 | The Tempest | Shakespeare | Shakesoc | English | |

| Kathputlian | – | Urdu Dramatic Society | Urdu | ||

| Mala-i-Ala | – | Urdu Dramatic Society | Urdu | ||

| 1938 | Scenes from A Midsummer Night’s Dream | Shakespeare | Shakesoc | English | |

| 1939 | Macbeth | Shakespeare | Shakesoc | English | |

| 1940 | Scenes from Julius Caesar | Shakespeare | Shakesoc | English | |

| 1941 | Henry VII | Shakespeare | Shakesoc | English | |

| 1942 | – | – | – | – | |

| 1943 | Arms and the Man | – | – | – | |

| 1944 | Candida | – | Shakesoc | English | |

| 1945 | As You Like It | Shakespeare | Shakesoc | English | |

| 1946 | – | – | – | – | |

| 1947 | – | – | – | – | |

| 1948 | Twelfth Night | Shakespeare | Shakesoc | English | |

| 1949 | – | – | – | – | |

| 1950 | A Comedy of Errors | Shakespeare | Shakesoc | English | |

| 1951 | Henry V (Info as in Jan 1953 AR) | Shakespeare | Shakesoc | English | |

| 1952 | A Midsummer Night’s Dream | Shakespeare | Shakesoc | English | |

| 1953 | Much Ado about Nothing | Shakespeare | Shakesoc | English | |

| A Midsummer Night’s Dream | Shakespeare | Shakesoc | English | ||

| Kanjus | Moliere | Dramatic Society | Hindi ? | ||

| 1954 | Much Ado about Nothing | Shakespeare | Shakesoc | English | |

| Macbeth | Shakespeare | Shakesoc | English | ||

| Mirza Jangi | – | Dramatic Society | Hindi ? | ||

| Lottery ka Ticket | – | Dramatic Society | Hindi ? | ||

| Mufloo | Upendar Nath Ashk | Dramatic Society | Hindi ? | Farce based on Ashk’s Jonk | |

| Comedy (?) | Moliere | Dramatic Society | Hindi ? | Based on Moliere’s Squire Lubberly | |

| Thriller (?) | Tadeusz Przeworsky | Dramatic Society | Hindi ? | Based on Polish play Vaclav, the Bandit | |

| 1955 | The Taming of the Shrew | Shakespeare | Shakesoc | English | |

| 1956 | Henry IV Part I | Shakespeare | Shakesoc | English | |

| 1957 | The Reluctant Doctor | Moliere | The Players | English | |

| The Dumb Wife of Cheapside | Ashley Dukes | The Players | English | ||

| Jor Tor | Hazrat Awara | The Players | Hindi | ||

| Khudkushi | Naqi Noor | The Players | Hindi | ||

| Kanjoos | Moliere | The Players | Hindi | ||

| Hamlet | Shakespeare | Shakesoc | English | ||

| 1958 | Arms and the Man | Bernard Shaw | The Players | English | |

| A Love’s Labour Lost | Shakespeare | Shakesoc | English | ||

| Moti Rakam | – | The Players | Hindi | ||

| Khudha Hafiz | – | The Players | Hindi | ||

| 1959 | The Importance of Being Earnest | Oscar Wilde | The Players | English | |

| Aap Bhi Chaliye | – | The Players | Hindi | ||

| Pagal | Romesh Mehta | The Players | Hindi | ||

| Rishta | Anton Chekhov | The Players | Hindi | ||

| Ek Raat | Rupert Brooke | The Players | Hindi | ||

| The Excellent History of the Merchant of Venice | Shakespeare | Shakesoc | English | ||

| 1960 | The Sladen Smiths | – | The Players | English | |

| Shivering Sharks | – | The Players | English | ||

| The Bear | Anton Chekhov | The Players | English | ||

| Spreding the News | Lady Gregory | The Players | English | ||

| Rishta | Anton Chekhov | The Players | Hindi | ||

| Sahil se Door | – | The Players | Hindi | ||

| Jahan Koi Na Ho | P. L Deshpande | The Players | Hindi | ||

| Khudkushi | Naqi Noor | The Players | Hindi | ||

| Ek Raat | Rupert Brooke | The Players | Hindi | ||

| The Merry Wives of Windsor | Shakespeare | Shakesoc | English | ||

| 1961 | The Eagle Has Two Heads | Jean Cocteau | The Players | English | |

| Kagaz ki Diwar | Ferenc Molnar | The Players | Hindi | ||

| Safar ka Saathi | – | The Players | Hindi | ||

| Dikhawa | – | The Players | Hindi | ||

| The Most Excellent & Lamentable Tragedy of Romeo | Shakespeare | Shakesoc | English | ||

| 1962 | A Night at an Inn | Lord Dunsany | The Players | English | |

| The Hiding Place | Clemence Dane | The Players | English | ||

| Winterset | Maxwell Anderson | The Players | English | ||

| Udhaar Devta | Rajinder Sharma | The Players | Hindi | ||

| Uncle Vanya | Anton Chekhov | The Players | Hindi | ||

| King Lear | Shakespeare | Shakesoc | English | ||

| 1963 | The Thieves’ Carnival | Jean Anouilh | The Players | English | |

| The Anniversary | Anton Chekhov | The Players | English | ||

| The Betrayal | Padriac Colum | The Players | English | ||

| Kamra No. 5 | Imtiaz Ali Beg | The Players | Hindi | ||

| Twelfth Night | Shakespeare | Shakesoc | English | ||

| Khirki Tord Hafta | Uggar Sen Narang | The Players | Hindi |

Appendix – II

| Name of the College | Name of the Group | Stage/Street |

| Dayal Singh College | – | Street |

| Deen Dayal Upadhya College | – | Street |

| Deshbandhu College | – | Street |

| Gargi College | Upstage | Stage/Street |

| Hansraj College | Hansraj Drama society | Stage-Hindi/English, Street |

| Hindu College | Ibdita | Stage/Street |

| IP College | Abhivyakti | Stage/Street |

| Jesus and Mary College | – | Street |

| Kamla Nehru College | – | Stage/Street |

| Kirori Mal College | The Players | Stage/Street |

| Lady Sri Ram College | Dramatics society | English – Stage |

| Lady Sri Ram College | Dramatics society | Hindi Stage |

| Lady Sri Ram College | Dramatics society | Street |

| Maitreyi | Abhivyakti | Hindi – Stage |

| Miranda House | Ariels | English – Stage |

| Miranda house | Anukriti | Hindi Stage/Street |

| Motilal Nehru college | – | Street |

| Ramjas College | Shunya | Stage/Street |

| SGTB Khalsa College | Ankur | Stage/Street |

| Shaheed Bhagat Singh College | – | Street |

| Sri Ram College of Commerce | Dramatics Society | Stage-Hindi/English, Street |

| St. Stephen’s College | Shakespeare Society | English Stage |

| St. Stephen’s College | Shakespeare Sabha | Hindi Stage |

| Venkateshwara College | – | English Stage |

| Venkateshwara College | Anubhuti | Hindi Stage/Street |

This paper is based on the research that I carried out for my M.Phil. dissertation on ‘Campus Theater Tradition: Continuity and Change’ in the Department of Modern Indian Languages and Literary Studies, University of Delhi. I am thankful to my teachers, especially Prof. T.S. Satyanath with whom the study on Campus Theatre took a concrete shape; as well as colleagues and students who triggered new thoughts and opened new directions. I sincerely acknowledge the anonymous reviewer whose comments and suggestions have enriched the quality of the paper.

[1] From 1920s till early 2000s.

[2] See Appendix I.

[3] See Appendix II for details.

References

Blackburn, Stuart and Vasudha Dalmia, Eds. India’s Literary History: Essays on the Nineteenth Century. New Delhi: Permanent Black, 2004.

Das, S.K., A History of Indian Literatures. New Delhi: Sahitya Akademi, 1995.

Gokhale, Shanta. Playwright at the Centre: Marathi Drama from 1843 to the Present. Calcutta: Seagull Books, 2000.

Gupt, Somnath. The Parsi Theatre: Its Origins and Development. Trans. and ed. Kathryn Hansen. Calcutta: Seagull Books, 2005.

Guran, Letitia. “US-American Comparative Literature and the Study of East-Central European Culture and Literature.” CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture, 8.1, 2006. <https://doi.org/10.7771/1481-4374.1295>, accessed on 26th June 2021.

Jacobus, Lee A., The Bedford Introduction to Drama. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1989.

Jain, Nemichandra. Indian Theatre: Tradition, Continuity and Change. New Delhi: National School of Drama, 1992.

Kapur, Anuradha. “Reassembling the Modern: An Indian Theatre Map since Independence.” In Nandi Bhatia edited, Modern Indian Theatre: A Reader, pp. 41–55. New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2009.

Lal, Ananda. “Historiography of Modern Indian Theatre.” In Nandi Bhatia edited, Modern Indian Theatre: A Reader, pp. 31–40. New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2009.

Richmond, Farley P., Darius L. Swann and Phillip B. Zarrilli. eds. Indian Theatre: Traditions of Performance, New Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, 1993.

Schechner, Richard. Between Theatre and Anthropology. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1985.

Singh, Jyotsna. “Different Shakespeare: The Bard in Colonial/ Postcolonial India.” In Nandi Bhatia edited, Modern Indian Theatre: A Reader, pp. 77–96. New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2009.

Spivak, Gayatri Chakravorty. Death of the Discipline. Calcutta: Seagull Books, 2003.

Talbot, Cynthia. Precolonial India in Practice: Society, Region and Identity in Medieval Andhra. New York: Oxford University Press, 2001.

Trivedi, Poonam and Dennis Bartholomeusz. eds. India’s Shakespeare: Translation, Interpretation and Performance. Delhi: Pearson Education India, 2005.

Totosy de Zepetnek, Steven. “From Comparative Literature Today Toward Comparative Cultural Studies.” CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture, 1.3, 1999. <https://doi.org/10.7771/1481-4374.1041>, accessed on 26th June 2021.

Welleck, Rene. “Crisis in Comparative Literature.” Concepts of Criticism, pp. 282-295. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1963.

Williams, Raymond. Drama in Performance. London: Frederick Muller, 1954.

Williams, Raymond. Problems in Materialism and Culture: Selected Essays. London: Verso, 1997.

Download PDF