Introduction[1]

Scholars are of the opinion that the unique multilingual and regional diversity of a country like India requires an interliterary study of its culture and texts. Amiya Dev in “Comparative Literature in India” articulates this point by drawing on Bhakti as a genre that has a variety of textual manifestations in various Indian languages. Dev observes, “There are many other similar literary and cultural textualities in India whose nature, while manifest in different other systems of a similar nature are based primarily on themes or genres, forms and structures observable in historiography” (5).

Comparative literature, as a discipline, facilitates a cross-cultural and interdisciplinary study of literature and culture. Comparative Cultural Studies, as defined by Steven Tötösy de Zepetnek, “is a field of study where selected tenets of the discipline of comparative literature merge with selected tenets of cultural studies, meaning that the study of culture and cultural products—including but not restricted to literature, communication, media, art, etc.” (Zepetnek 45).

Research on this plurality of representations has been conducted by Satyanath (2010) while studying the characteristics of Kannada literature where he explains: “Literature is first of all oral, collective, and narrative in nature and often existed only in performance” (4). Therefore, while the history of Kannada literature begins with documenting the written literary traditions like the Jaina courtly style (Champu) it also comes to incorporate into this framework the oral, performative dimensions of a literary text as evident in the poems of the Vachana, Ragale and Shatpadi genres of Karnataka. It becomes clear that to map out a literary history of a country like India, it is required to understand that a literary text may exist in different forms (written, oral, or performance) and may also be a part of the history of more than a single sect, language, or religion.

The above-mentioned ‘textual’ movements can also be observed in the traditional storytelling traditions of India. A study of such picture showmen tradition (whether secular or religious) brings forth discussions on the text in its oral, written, and performance mediums. The presence of a single narrative in several media is interesting for two primary reasons. Firstly, such transmedial narratives challenge the notion of the supremacy of the written, especially within the Indian public sphere(s). Second, they throw light on the nature of “texts” in precolonial India as “tellings” whose ur text is untraceable. The Indian public sphere in the pre-modern times comprises several spaces that sometimes intersect and overlap. Spaces such as the courts, temple/mosques, village squares, fairs, universities, and professional guilds carried out this complex exchange and transfer of texts in their myriad forms, constantly erasing the neat boundaries between the “written,” “painted,” or “performed” that modern scholarship has largely depended on to carry forth discipline-centric analysis of the past. This paper argues that a transmedial approach, where the subject of scrutiny is not just the “written” but also the “oral” and “performative” texts, offers a different angle to the study of what constitutes as Indian literary “texts” of pre-modern times.

There are references to picture showmen in ancient Indian texts as shaubhikas(roughly translated to mean “shadow playman”) in Patanjali’s Mahabhashya (2nd century B.C.E.). Other closely related terms are mankhas and yamapattakas, who according to Iravati were those “who used to describe the pictures painted on a board carried by them from one place to another; of yamapata, a similar art, wherein the artist described the scenes of the life after death painted on a board or scroll” (25). Buddhist and Jaina literatures also contain several references to this tradition of itinerant picture storytellers. Iravati mentions a list of entertainers provided in the Aupapatika Sutra, “Similar reference is found in the stories of Sramanopasaka and Megha Kumara Sramana. Maniyara Sresthi constructed a large citra–sabha with beautiful paintings on cloth decorating the hall. Several theatre artistes including mankhas were appointed there on payment to entertain people” (25). In the Buddhist text Divyavadana, Skelton notes that King Bimbisara commissioned a painting of the Buddha on a piece of cloth. The artists failed the task following which the Buddha allowed his shadow to fall on the cloth, and the outline was then filled with colours.

Victor Mair traces the roots of storytelling through paintings to ancient India that were later transmitted across Asia via the silk route(s). In his estimation of the transportation of cultural elements specific to Buddhism from ancient India to Tun Huang in China, Mair notes that it was an amalgamation of Indian, Graeco-Buddhist and Irano-Buddhist art that finally reached Tun Huang. He quotes Liu Man-tsai to illustrate this point “Traders, missionaries, envoys, and soldiers, who passed through Kucha, were also bearers of culture, and so there arose a syncretism that was evident in art” (Mair 50). Mair also states that, “Central Asia’s ties with the rest of the world became especially intense during the fifth and seventh centuries. The Sogdians were prominently involved in transmitting elements of various cultures along this route” (50). The technique of using continuous pictorial narratives in Sogdian art is testimony to the significant role Sogdiana played in the transmission of such traditions along the silk route(s). Such routes must be imagined as tiny veins connecting to the larger arteries through which material, in its tangible and intangible forms, made its way into a variety of linguistically and culturally diverse worlds.

Furthermore, Mair’s scholarship on Chinese vernacular literature during the Tang dynasty makes an interesting connection between the prosimetric style employed by such writers, which he believes to have originated from the Buddhist picture showmen, or transformation texts called chuanpien. This insight provides one example of the oral/performative text that influences the style and themes present in the written, which may usually go unnoticed. An investigation of oral, visual, and performative texts may provide further information on the processes of building and transferring of knowledge. As such, an in-depth analysis requires further research; this paper shall however limit itself to examining three picture storytelling traditions, the Phad of Rajasthan, the Patas of West Bengal, and the narrative Thangka of the Manipa tradition of Tibetan Buddhism, and the diverse techniques used by the performers to represent the particular story, to study how it affects the narrative structure of the painting as well as its narration.

Language, Text, and Representation

A text is commonly defined as a “written work” or “the main body of a book as distinct from illustrations.” Therefore, we arrive at the conclusion that any body of work, any symbol that uses “language” and is different from a graphic illustration can be called a text. Thus, a text may exist in the form of writing on a piece of paper, literary works, a caption under a photograph (Barthes, Image-Music-Text 79). The domain of the text is the language spoken or written.

The intention in this paper is to understand what characteristics and features define a text, whether written or spoken, and its relationship with other mediums, such as images. This enquiry is based on discussions held amongst art historians and literary critics on the distinguishing features of an image and a text and in the many ways in which the text and image complement each other to create a representation. How for instance, when we view an image, we immediately try to arrive at its meaning through a text or language or how we formulate an image in our minds whilst reading a text that brings about a more wholesome meaning.

According to W.J.T. Mitchell, “the interaction of pictures and texts is constitutive of representation as such: all media are mixed media, and all representations are heterogeneous, there are no “purely” visual or verbal arts, though the impulse to purify media is one of the “central utopian gestures of modernism” (95). Stuart Hall, in the introduction to Representation: Cultural Representation and Signifying Practices, defines representation in terms of language, “In language, we use signs and symbols—whether they are sounds, written words, electronically produced images, musical notes, even objects—to stand for or represent to other people our concepts, ideas and feelings. Language is one of the ‘media’ through which thoughts, ideas and feelings are represented in culture. Representation through language is therefore central to the processes by which meaning is produced” (1).

Having equipped myself with these ideas, I turn to debates on concepts that connect literature to other media where I have found studies on intermediality most helpful. Werner Wolf explains the usage of transmediality in situations where “literature as a medium shares transmedial features with other media” (“[Inter]mediality and the Study of Literature” 4). T.S. Satyanath’s (“Processes and Models of Translation”) tripartite approach, encompassing the scripto-centric, phono-centric and body-centric domains, supports this transmedial approach in studying medieval Indian literature. He notes, “The schema of precolonial representations included an overlapping of scripto-centric (manuscript), phono-centric (orality) and body-centric (performances, painting and sculpture) systems of representation.” Satyanath also suggests that we bring texts here belonging to a ritualistic or performative setting into the fold of literary studies.

Three scroll painting narrative traditions, namely the Phad of Rajasthan, the Patas of West Bengal and the narrative Thangka of the Manipa tradition of Tibetan Buddhism will be examined as examples of transmedial texts. Most of my understanding of the Patua, Bhopa and Manipa/Buchen tradition stem from the data I collected for my M.Phil. dissertation back in 2010 (Angmo). I was most fortunate to be appointed as programme coordinator for “Akhyan: A Celebration of Masks, Puppets and Picture Showmen Traditions of India,” an event organised by Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts and Sangeet Natak Akademi (held between October and November, 2010) that brought, various traditional performers, and picture storytellers from Rajasthan, Andhra Pradesh, and West Bengal in particular to Delhi.[2] Scholars such as Kavita Singh, John D. Smith, Aditya Malik, Roma Chatterji, Jyotindra Jain and Komal Kothari to name a few have dealt in detail with the Patua and Bhopa in their respective works and have greatly added to my perspectives on the traditions. Babulal Bhopaji and his family, Sukharam Bhopaji, Prabir Chitrakar Rani Chitrakar, Karuna Chitrakar, and Kalyan Joshiji, patiently guided me through the rich visual and oral labyrinths of their respective traditions.

Pata Chitra Tradition

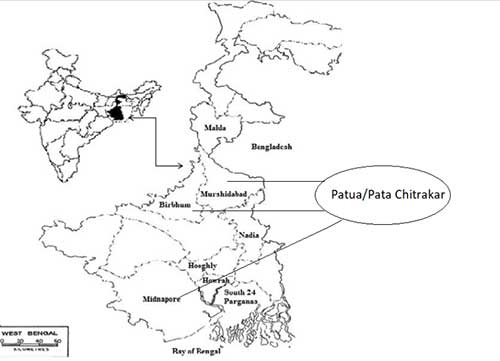

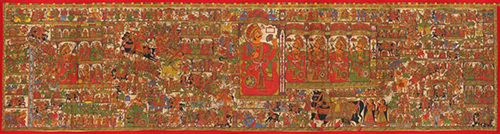

Pata or Pata Chitra is a vertical scroll painting that depicts a variety of narratives ranging from the religious, secular, to the political in content. These Patas are painted as well as sung by the men and women Patuas belonging to the villages in the Medinipur, Birbhum, and Murshidabad districts in West Bengal (see Figure 1).

They are also known as Chitrakars meaning “picture-painters.” Sarojit Datta, in Folk Paintings of Bengal, traces the antiquity of the Pata Chitra tradition to the Brahmavaivarta Purana where the term Chitrakara can be found classified under the Naba Sakya group. This text states that Sutradhara, Kamasakara, Svarnakara, and Chitrakaras were born as a result of the union between Vishwakarma, the celestial architect, and Gritachi. The myth also recounts the expulsion of Chitrakaras from the Naba Sakya caste as the Brahmins objected to their inclusion because of their profession. Chunnilal Chitrakar of Panuria village (Birbhum district of West Bengal), explains this incident to Sarojit Datta through a story (Datta 9).

Source: Author

Their forefather Vishwakarma once painted a portrait of Shiva without his consent, which angered the God terribly. One day, while walking past Shiva, Vishwakarma hid his paint brush in his mouth to avoid confrontation. When Shiva discovered that Vishwakarma had contaminated the brush, he cursed him and his future descendants to a life outside the caste system.

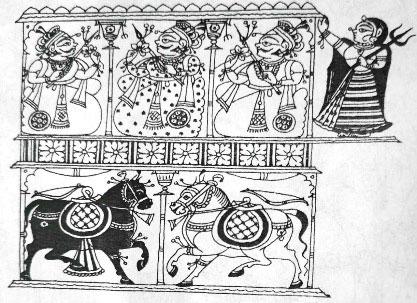

The Patuas or Chitrakars are Hindus or Muslim, or both in some cases. Women in this community also actively participate in the painting and performance of the Pata today (see Figure 2). Roma Chatterji observes that, “The adoption of ‘Chitrakar’ as a title went hand-in-hand with the recognition of Patuas as ‘folk artists’, rather than ‘folk performers’ for whom displaying scrolls and singing was a form of begging” (9). Chatterji further notes that the Patuas or Chitrakars hailed from different castes and subcastes who in the recent past had miscellaneous jobs such as cow leeching, cardsharping, performing with bears, snakes, monkeys, and goats. Some of them were even skilled in performing medical procedures such as abortions and cataract operations. Overall, we are told that the hierarchy of castes and subcastes among the Patuas are more fluid than their ambivalent religious beliefs (Chatterji 9–10).

The Patua or Chitrakar paints the images on paper supported by a long piece of cloth (an old saree) stuck behind the paper. They use organic pigments, for instance, the colour red from Chinna Sindur, black from charcoal, orange from Mete Sindur and white from chalk. All these colours are then mixed with appropriate proportions of tamarind seed paste, Bel fruit, egg shell and gum from the Neem tree to make the paint. The Patua or Chitrakar begins by drawing the outlines of the figures, trees, and other objects. These images are then filled with colours, following which the designs for the borders of each panel are rendered.

As far as themes are concerned, the Pata offers a variety of narratives. Some of the Patas dealing with religious narratives are the Rama Lila, the story of Durga, Manasamangala, Gazi Pir, and Chaitanya Mahaprabhu. Contemporary narratives such as The Tsunami, Murder of Indira Gandhi, 9/11 Attack on the World Trade Center, Communal Riots, HIV/AIDS awareness have also been painted and sung by the Chitrakars.

The performance of the Pata is called Pata Dikhaba which means “showing the Pata.” The narrow vertical scroll is unrolled panel by panel thereby showing scenes that correspond to its narration. The Patua or Chitrakar goes from village to village and perform wherever they might be received by an audience.

The visual representation of the story of a Pata can be easily read and followed by a reader who is familiar with the story. The narrative follows a top-down direction, moving in a linear pattern, guided by the words sung by the Patua or Chitrakar.

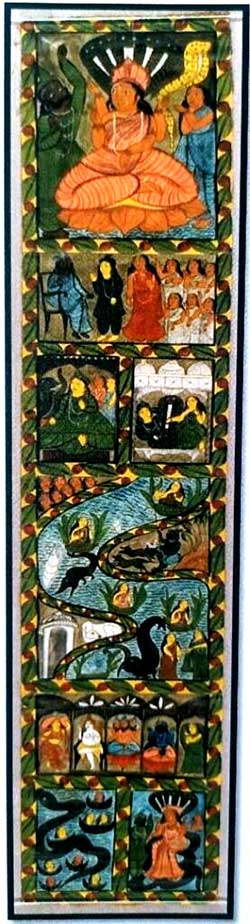

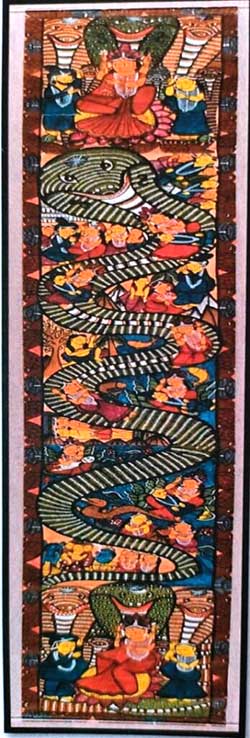

We can take as an example, the popular story of Manasa Devi as displayed on a Pata and its narration to better understand the narrative mode involved. Manasa Devi is the goddess of snakes and worshipped as Bishahari or “remover of poison.” Among the many birth and origin stories centred around this goddess, Kaiser Haq outlines the most well-known one in this manner, “Like many supernatural beings Manasa is born magically, of semen involuntarily ejected by Shiva onto some object; different versions mention different objects” (39). Haq describes Parvati’s jealousy (or Chandi) when Shiva brings his daughter home. Mistaking Manasa for Shiva’s mistress, Chandi “gouges” one of her eyes out, while the former knocks her out with her powerful gaze. For this reason, Shiva creates Neta who acts as Manasa’s sister/adviser (39). The Manasa story that Patuas perform gives an account of how she forcefully diverted a merchant, Chand Sadagar’s devotion and worship of Shiva to herself. Manasa Devi is an important goddess in East and West Bengal, and parts of Jharkhand, Assam, and Chhattisgarh, who protects her devotees from snakebites, and brings them prosperity.

Pata–1

Source: www.learning

objects.wesleyan

.edu/naya.html

Ananda Coomaraswamy and Sister Nivedita, in Myths of the Hindus and Buddhists with reference to this legend, state “The legend of Manasa Devi, the goddess of snakes, who must be as old as the Mycenaean stratum in Asiatic culture, reflects the conflict between the religion of Shiva and that of female local deities in Bengal. Afterwards Manasa or Padma was recognised as a form of Shakti (does it not say in the Mahabharata that all that is feminine is a part of Uma?), and her worship accepted by the Shaivas. She is a phase of the mother-divinity who, for so many worshippers, is nearer and dearer than the far off and impersonal Shiva, though even he is, in these popular legends, treated as one of the Olympians with quite a human character” (323–330). Assimilation of local deities into the larger Hindu pantheon or vice versa is a common feature of Indian religious systems that reflects the multiplicity inherent in its pluralistic traditions. Two Patas depicting the story of Manasa Devi and Chand Sadagar (see Figures 3 and 4) will be studied here to point to the narrative structure as well as oral/visual variety in the Patachitra tradition.

In both paintings, the narrative begins with the topmost panel depicting goddess Manasa surrounded by snakes and with Chand Sadagar on her right, arrogantly holding a hetal stick, threatening to kill any snake that comes near him. On her left is Behula, the recently widowed wife of Chand Sadagar’s seventh son, Lakhindar, praying or pleading with Manasa Devi. Since Chand Sadagar refused to worship Manasa, she killed all his sons. Behula is the figure of pity and moves the gods with her tears and determination to bring her husband back to life. She makes a raft of banana leaves and carries her dead husband’s body along to plead with the divine. The second last panel in both the paintings has Manasa Devi and Behula flanking the holy Hindu trinity: Shiva, Brahma, and Vishnu.

Pata–2

Source: www.learning

objects.wesleyan.

edu/naya.html

This panel marks Manasa Devi’s connection with the more popular gods and sanctions her demand to be worshipped by the more affluent merchant class like that of Chand Sadagar. Both paintings repeat the topmost panel to depict this moment, with Chand Sadagar’s expressions now conveying reverence. The story ends with the gods reviving Chand Sadagar’s sons. These two representations of the same story could be easily mistaken for two different tales if one did not look more closely.

While the first painting (Figure 3) focuses on the first half of the story, the second (Figure 4) painting’s creative use of the snake’s movement to depict the meandering curves of a river as Behula journeys through it is highlighted. Here, we get a glimpse of the unique integration of the visual and verbal worlds as the artist freely employs his imagination to depict scenes with a mark of his individual aesthetics. The oral narration or song that accompanies the text moves in a linear fashion and the painting is also unrolled from the topmost panel to the last. Scenes are contracted or expanded, sometimes stacked one below the other or placed next to each other, depending upon how the artist sees the narrative unfolding in her/his mind. These details complicate the simple top-to-bottom sequence in the absence of the Chitrakar/Patua. Furthermore, different artists choose which scenes to depict and which to leave out or how a particular scene could be visually represented, resulting in a wide variety of Manasamangala Patas. The topmost panel of these Patas almost always bears the image of Manasa Devi. Other scenes of importance that aid in identifying the visual text is the flowing river and the three gods that grant Behula’s wishes. Keeping these details in mind, we can state that the Patachitra usually depicts the narrative in a linear fashion owing to its narrow, vertical shape with sudden breaks in the flow of our ‘reading’ of the visual text due to the breaking up of the space into two or three scenes.

The Phad (Par) Tradition

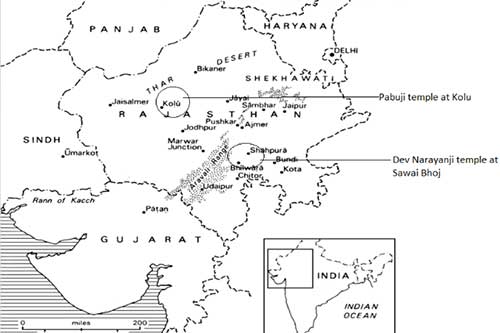

In Rajasthan, the large, horizontal Phad or Par scroll paintings depict epics of local gods (lokdevta) and consolidate the relationship between different communities: the singer of the Phad, the maker of the Phad, and the devotees of the gods of the Phad. Of the many gods worshipped in this manner, the epics of Pabuji and Dev Narayanji are the most popular. As is the case with most of the local epics, Pabuji and Dev Narayanji are worshipped for their bravery; in fact, it is the sacrifices they make (including giving up their lives) that are remembered, alongside their efforts to uphold the pride of their clan. The Phad for these reasons is a sacred object, a mobile shrine that travels to the locations of its devotees. The Bhopa is the bard that sings the events depicted in the Phad. He functions as a priest and narrator of the epic. It is also important to note that the Bhopas are priests and performers of only one epic. Each epic has its own unique set of scroll painting, priest-performer and clientele. All the scroll paintings, however, are painted by the artists of the Cheepa community called the Joshis. Therefore, the layout of the Phad or the colour and style used by the Joshis are similar across these epics. These paintings are accompanied by musical instruments such as the ravanahatto in the case of the Pabuji tradition and the jantar in the Dev Narayan tradition (see Figure 5 for the spatial distribution of Pabuji and Dev Narayanji traditions).

Shivkumar Sharma provides a brief outline of the method used for painting the Phad. “A Par is painted on Khadi cloth only and the usual measurement is 35’x 5’ for the Dev Narayanji theme and 15’x5’ for the Pabuji theme” (45). He further explains that the artists first draw a rough outline of the Phad in yellow which is called kachi likali. The artists then fill the rest of the colours according to tradition, carefully using a separate brush for each colour. The last colour to be filled in is black (or syahi) which makes all the objects painted on the Phads tand out. When the painting is ready, both the Bhopa and the patron arrive at the painter’s home. Here, after a few rituals, the last touch is given to the painting. The “sight-giving” ritual is said to awaken the deity who comes to live in the Phad from then on and leaves the painting only after it is worn out and immersed in a water body after a few rituals. This ritual is called “thandi karni” (cooling), which symbolises that the Phad was hitherto hot or alive with the deity’s energy and now becomes cold as he leaves it.

The epic of Pabuji recounts the events from the life of a Rajput warrior called Pabuji. According to the epic, Pabuji was born in Kolumund around the fourteenth century to Dhadhal, the leader of the Rathor clan through his marriage to an apsara (celestial dancer) called Kesarpari who transforms into a tigress to feed Pabuji. Kesarpari leaves the palace the moment her husband discovers her in this form, and returns later as Kesar Kalami, Pabuji’s horse. The narrative praises Pabuji’s beauty and strength, comparing him to Ganesha, Kalika, and Hanuman. He is also the reincarnation of Lakshmana and travels to Lanka to defeat Ravana and brings she-camels to Rajasthan (from Lanka) for the first time. He is worshipped today as the protector of land and cattle, primarily by the Rebari tribe who rear camels.

The earliest Pabuji text is said to have been written by the Charans, a community of poets to the royal Rajputs of Rajasthan. This text was called the Pabuprakasha. Somehow one of these texts found its way into the precincts of the Pabuji temple at Kolu. The lower caste Nayak priests learnt the epic and taught it to the Bhopas who also belong to the same caste (Smith 14). The story of the epic narrates that there were seven Nayak brothers who were servants of Ano Vaghelo, a powerful Rajput. Once during a famine these Nayak brothers killed an animal and ate it which angered Ano Vaghelo’s son. A fight broke out between the Nayak brothers and Ano’s son which ended in the death of the latter. The brothers fled and sought refuge in many king’s courts, but were turned away in fear of angering Ano Vaghelo. It was only Pabuji who accepted their services. In the latter half of the epic, Pabuji also assists the Nayak brothers to slay Ano Vaghelo.

The epic of Dev Narayanji begins with Leela Sevdi, a widow who gives birth to a baby boy with a tiger’s head called Bagh Rawat, who married twelve women and gave birth to twenty-four sons. The eldest of these sons was Sawai Bhoj. His wife Sadu Mata gave birth to Dev Narayanji who was an incarnation of Lord Vishnu. Like Pabuji, Dev Narayanji earns the status of a deity because of the vast number of battles he fought and for his subsequent death at an early age.

The origin of this story is accounted for by a tale. As told to me by Sukharam Bhopaji, the first Bhopa, Chochu Bhat was Dev Narayanji’s genealogist. On the fateful day that Dev Narayanji was killed at battle and was on his way to heaven, his wife caught hold of his garment, a piece of which came off in her hands. This piece of cloth contained images from the life of Dev Narayanji which was utilised by Chochu Bhat to sing the stories of the hero-God Dev Narayanji. Devotees of Bhagwan Dev Narayanji mostly belong to the Gujjar community while the priests of the Phad may belong to the Gujjar, Balais, Rajput, or Kumbhar communities.

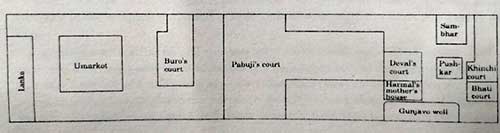

Visually, these epics may appear identical to new eyes as they follow a similar pattern. The Dev Narayan Phad is much larger than the Pabuji Phad. To understand the sequence of the events depicted on the Phad, I borrowed John D. Smith’s Phad and schematic layout of the Pabuji Phad (see Figures 6 and 7). We discover that scenes from the epic are depicted from a geographical point of view. The Phad, like a giant map shows the courts of several figures of the epic with Pabuji seated at the centre, with space overruling time in this visual text.

Source: https://sarmaya.in/spotlight/inside-the-magical-world-of-rajasthans-phad-paintings/

Source: Smith 2005, 31

Source: Smith 2005, 63

The performance of the Pabuji Phad is called Pabuji riparvaro, where the Bhopa narrates and sings episodes from the epic. We can take one of these episodes known as “The Episode of the Hare” to demonstrate how the Bhopa unlocks this visual text that is otherwise buried in actions and symbols inaccessible to the untrained or uninitiated eye (see Figure 8). Very briefly, this episode shows Pabuji’s brother Buro Raja’s conflict with the Khinchi king Sarangde. Buro Raja, while on a hunt, had wounded a hare seeking refuge in the Khinchi king’s palace. Buro Raja proclaims war against the Khinchi king for not giving up the hare. Pabuji and his courtiers join this battle where Sarangde the Khinchi king is killed. In order to maintain peace, Pabuji and his brother Buro Raja wed their sister Pema to Sarangde’s son, Jindrav Khinchi. This marriage, as we learn in later episodes, does not quell thoughts of revenge in Jindrav Khinchi who eventually kills Pabuji.

Source: Smith 2005, 65

According to Smith, this episode has been depicted in two scenes on the Phad, the first one illustrates King Buro’s court at Kolu in the centre of the Phad and the second representing the battle has been painted in Khinchi’s court located in the extreme right corner of the Phad (see Figure 9). The second scene also has the image of a hare being chased by a dog below which we find Pabuji and Sarangde Khinchi in action on the battlefield. The narrative of the Phad thus depends upon the activation of the images by the constant movement of the Bhopa, who explains (for instance, this episode) by repeatedly pointing at the characters seated in their courts or at the hare or the battle scene to narrate this episode.

The Bhopa can repeatedly point to a single figure (like that of Pabuji or Dev Narayanji at the centre), while he sings long verses about the character and their actions. During performances that extend late into the night, the Pabuji Bhopa sings, recites, and dances while his assistant (mostly his wife) sings some parts while holding a lamp (diya) to illuminate scenes on the Phad. The Bhopa of the Dev Narayan Phad differs in many ways from the Bhopa of the Pabuji epic. For example, the Bhopa of the Dev Narayan epic wears a yellow turban symbolising Sawai Bhoj with a black thread signifying Saili Rani, one of the wives of Dev Narayan. A pointing stick made of peacock feathers signifies Khamcho Rani another wife of Dev Narayan. Apart from being an all-male performance, one of the distinguishing features of the Dev Narayan Bhopa is the jantar, a musical instrument made from hollow pumpkins.

The Narrative Thangka

The most common name for a scroll painting in Tibetan is Thangka, which means something that is rolled up. Shiv Kumar Sharma provides a detailed description of the process of Thangka making and the different types of Thangka in his book Painted Scrolls of Asia. Thangka is also called Thangku where thang means spread and ku means image. Rabris is another name given to scroll painting where rab means a piece of cloth and ris means rimo or drawing. These Thangkas are usually vertical and narrow at the centre and wide at the ends supported by two rods at the top and the bottom. Thangkas contain images that are either painted (Thangka bris-than) or embroidered (Thangka gos-than). The first type of Thangka is more common. The size of a Thangka today can vary from a regular A-4 size sheet to 45-55 metres that are unrolled on mountainsides or from the high walls of a monastery (Sharma, 66-67). Today one also comes across a third type which contains photographs of distinguished religious leaders.

The process of painting a Thangka begins by first conducting a few rituals presided over by a lama or monk. (Sharma, 66). A white cloth is stretched and stitched onto a wooden frame and the surface is prepared by applying a light mixture of glue to ensure all pores are covered. The artist then draws the outline of the border, followed by a rough sketch of the deity. They then paint the rocks, clouds, water, hills, beginning with light colours and later with darker colours. The deity is the last object to be painted. The colours are extracted from minerals mixed with thin glue, although today, artificial paints are also used. Once complete, the Thangka is stitched to a long piece of cloth, mostly silk and the letters Om Ah Hum inscribed behind the central deity. The Thangka becomes a sacred object after this inscription and a few rituals conducted by a lama. The theme of a Thangka can range from depicting Buddhas, Arhats, protector deities, mandalas, lineages of sects, and narratives associated with the religion.

A Thangka is used as a shrine and is an object of daily veneration that is hung on the walls of temples, monasteries and at home. Thangkas are also used for meditation where the practitioner meditates on the deity features in such paintings. Thangkas also function as mobile shrines that could be carried from one place to another.

Source: Waddell 1958, 543

There were a number of itinerant religious storytellers who travelled from one pilgrimage site to another, stopping and reciting tales from the lives of Buddha Shakyamuni and other well-known personalities of Tibetan Buddhism. These storytellers were called Manipa or reciters of Mani, the mantra of Avalokiteshvara (Om Mani Padme Hum), who is revered as the Boddhisattva of compassion.

According to Hanna Havnevik, the Manipa tradition may have begun around the 14th century. Bhuchen Gyurmey, who hails from the Golok area in Tibet, is considered to be the last Manipa or Lama Mani who passed away in 2004. This tradition of picture storytelling is still alive in Pin Valley, Spiti, Himachal Pradesh. Among the early Western scholars who showed interest in Thangkas and the Manipa tradition were Guiseppe Tucci and L.A. Waddell. Tucci covers a large amount of material on Thangkas in general in his magnum opus Tibetan Painted Scrolls (1949) where he talks a little about the Manipa tradition, “The custom survives in Tibet, in the fairs, places of pilgrimage and bazaars of the chief cities one frequently meets itinerant lamas or laymen, who sing to a devoutly spellbound audience wonderful stories about Padmasambhava and the glories of Amitabha’s heaven, showing as they sing, on large Thangkas they unroll, the pictorial representation of the events or miracles they are relating.” These stories called rnamthar are life stories that detail the exemplary spiritual path taken by famous personalities. The word rnamthar is short for rnam par thar pa, which roughly means “completely liberated.” The Manipa persuades the crowds to recite the mantra of Avalokiteshvara between regular intervals. Such a collective recitation of the mantra is believed to increase spiritual merit.

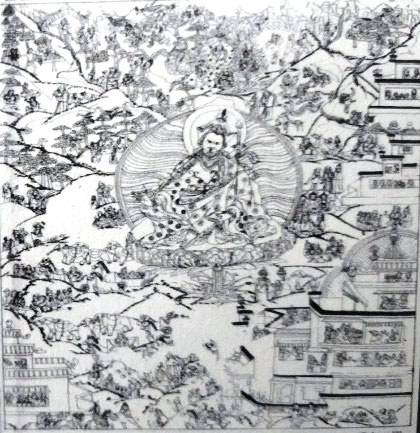

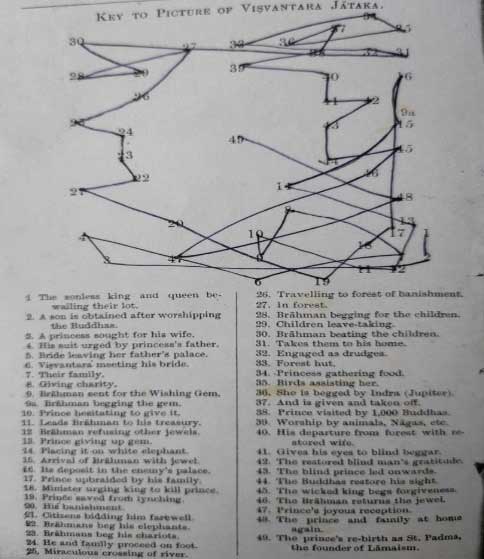

Much like the Phad, the structure of the narrative Thangka is difficult to decode. L.A. Waddell, in The Buddhism of Tibet or Lamaism (1895), takes a Thangka depicting the Vishwantara or Vessantara Jataka and numbers the actions around the central figure to understand the movement of the narrative. This Thangka has Guru Padmasambhava, the eighthcentury Mahasiddha seated at the centre as the reincarnation of Prince Vishwantara (see Figure 10).

In order to map the narrative sequence of this Thangka, an attempt has been made to look for visual clues that could be obtained in the pattern or diagram to help unlock the mode of visual narrative utilised by such Thangkas. Looking at this diagram (see Figure 11) there are three possible interpretations of the mode of visual narration used by the Tibetan narrative Thangkas:

Source: Waddell 1958, 542

- Vertical or upward movement: The narration begins to the left of the central figure, on the lower half of the Thangka. It then moves to the left and follows a criss-cross upward pattern. This pattern seems to suggest the viewer’s following a vertical path that may be connected to one’s spiritual elevation (or Sadhana in Sanskrit) as the story develops. The Thangka is after all an object whose main function is to transport the viewer into a spiritual realm. This pattern, however, does not seem to have been followed for the events that unfold on the right side of the Thangka.

- Another possible interpretation is that the narrative of the Tibetan Thangka just simply follows a sacred geography. Repeated attempts to link the sacred geography with the Thangkas have not been successful in the present state of understanding. However, linking sacred geography and Thangkas, I believe, probably provides a clue to understanding of the narrative Thangka paintings.

- The third interpretation perhaps brings us closest to unlocking the narrative mode of Tibetan Thangkas. If we take a close look at the diagram and ignore the occasional zipping across of some scenes on the Thangka, we can clearly see a radial or circular movement of the narrative. It seems as though our reading of the scenes in successive order takes us on a clockwise circumambulation or pradakshina of the central figure. Circumambulation, as we know, forms a central part of the rituals one follows while offering prayers at a sacred shrine. The narrative mode of the Thangka, therefore, takes its readers on such a spiritual tour of the story as well as completes one cycle around the central deity.

Vidya Dehejia (1998), in her paper “Circumambulating the Bharhut Stupa: The Viewer’s Narrative Experience,” describes the narratives from different Buddhist stories that have been depicted on the walls surrounding the Bharhut stupa and how they enriched the experience of the devotee as they offered their prayers while circumambulating the stupa. One can also see a close connection between the structure of such narrative Thangkas and a medallion depicting the Chaddanta Jataka from the Stupa at Amaravati, Andhra Pradesh (see the numbered sequential development of the narrative in Figure 12).

The main focus of this paper has been to understand the diverse techniques of visual narration that have been employed in the Phad, Pata, and Thangka. Each scroll painting applies its visual text to a space that relies on the size and shape of the work. For the Pata, the action flows from top to bottom, the Phad and Thangka adhere to more complex rules that are not easily decipherable. This is not to state that the Pata is simpler, since Chitrakars/Patuas have the freedom to experiment with the text in their mind and how it finally expresses itself on cloth. In a short video titled “Sita’s Ramayana” on Tara Books’ website, Moyna Chitrakar says that “the song comes first and then the scroll.” There are a variety of songs and an equal diversity in their visual representations, all requiring a closer look before making such assumptions. The integration of song, painting, and dance in picture storytelling traditions educates the viewer/listener of a particular episode/story that does not require a written text.

The presence of narratives in the Pata, Phad, and Manipa/Buchen traditions points to a complex matrix constituting multiple public spheres and their interactions giving them a unique blend of pluralistic knowledge systems that form their literary framework. Each of the traditions discussed here works primarily in an oral and performative space, catering to the religious and cultural belief systems of the masses that did not have access to written material, especially in the precolonial period. By employing narratives lodged in different mediums, the picture showmen traditions offer an alternative mode of understanding the movement and transformation of texts across different public spheres. These public spheres are the open village and town squares, and religious festivals frequented by locals who today actively participate in the promotion of such traditions by uploading videos of such performances on YouTube and other online platforms. For instance, the Internet today offers a space for both performances by the Bhopas of Dev Narayanji and Pabuji and the bhajans sung by upper caste devotees on YouTube. Whether these bhajans borrow material from the Bhopa tradition and what we might uncover in this process needs further investigation. Similarly, many regional websites provide information on such traditions in regional languages where narratives seemed to be borrowed from the picture showmen tradition to showcase the cultural identity of the particular area and their people. These observations compel one to look at picture storytelling traditions comparatively along the temporal and spatial axis, showing the spatiality of distribution of a particular tradition on the one hand, while also understanding how these three traditions evade a temporal analysis. Analysing the depth and complexity of these traditions in a single paper is a task that cannot be accomplished without running into generalisations. Therefore, the goal here has been to highlight the diverse structural spaces that narratives inhabit, in words, images, and performance, with an attempt to display the transmedial features of picture storytelling traditions, where the role of the storyteller is central to its performance.

I am extremely grateful to all the artists who generously shared their knowledge with me during “Akhyan: A Celebration of Masks, Puppets and Picture Showmen Traditions of India”, 2010. All photographs were taken by the author, unless specified.

[1] I am grateful to Prof. Subha Chakraborty Dasgupta and Prof. T.S. Satyanath for providing their suggestions and valuable feedback. A large portion of this paper has been taken from my M.Phil. dissertation titled Scroll Painting Narrative Traditions: A Study of Tibetan Scroll Painting Narratives, 2011. Acknowledgements are also due to the anonymous reviewer for comments and suggestions.

[2] I thank Prof. Molly Kaushal, former head, Janapada Sampada, IGNCA, New Delhi for giving me the opportunity to learn as a project assistant for “Akhyan: A Celebration of Masks, Puppets and Picture Showmen Traditions of India”, 2010.

References

Angmo, Nilza. Scroll Painting Narrative Traditions: A Study of Tibetan Scroll Painting Narratives. M.Phil. dissertation, Department of Modern Indian Languages and Literary Studies, University of Delhi, 2011.

Barthes, Roland. “An Introduction to the Structural Analysis of Narrative” New Literary History 6, 1975.

Barthes, Roland. Image-Music-Text. Trans. Stephen Heath. London: Fontana Press, 1977.

Blackburn, S.H. et. al (eds.). Oral Epics in India. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1989.

Chatterjee, Roma. Speaking with Pictures. Folk Art and the Narrative Tradition in India. New Delhi: Routledge, 2012.

Coomaraswamy, Ananda, K and Sister Nivedita, Myths of the Hindus and Buddhists. London: George G. Harrap and Company, 1913.

Dehejia, Vidya. “Circumambulating the Bharhut Stupa: The Viewer’s Narrative Experience.” Picture Showmen: Insights into the Narrative Tradition in Indian Art, Marg, Vol. 49, No. 3 (1998). 9-22.

Dehejia, Vidya. “On Modes of Visual Narration in Early Buddhist Art.” The Art Bulletin, Vol. 72, No. 3 (Sep., 1990). 374-392.

Datta, Sarojit. Folk Paintings of Bengal. New Delhi: Khama Publishers, 1993.

Dev, Amiya. “Comparative Literature in India.” CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture 2.4, (2000) <https://doi.org/10.7771/1481-4374.1093>, accessed 26th June 2021.

Dollfus, Pascale. “The Great Sons of Thang Stongr Gyal Po: The Buchen of the Pin Valley, Spiti.” The Tibet Journal, Vol. 29, no.1. 9–32.

Hall, Stuart. Representation: Cultural Representation and Signifying Practices. London: SAGE Publications, 1997.

Haq, Kaiser. The Triumph of the Snake Goddess. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2015.

Iravati. Performing Artists in Ancient India. Delhi: D.K. Printworld, 2003.

Jash, Pranabananda. “The Cult of Manasa in Bengal.” Proceedings of the Indian History Congress, Vol. 47 (1986). 169–177, http://www.jstor.org/stable/44141538, accessed 26th June 2021.

Joshi, O.P. Painted Folklore and Folklore Painters of India. Delhi: Concept Publishing Company, 1976.

Kapoor, Kapil, and Avadhesh Kumar Singh (eds.), Indian Knowledge Systems. Shimla, IIAS, 2005.

Kapstein, Matthew T. “The Indian Literary Identity in Tibet.” In Sheldon Pollock edited, Literary Cultures in History: Reconstructions from South Asia. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2003.

Mair, Victor. Painting and Performance. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1988.

Mair, Victor. “The Buddhist Tradition of Prosimetric Oral Narratives in Chinese Literature.” Oral Traditions, Vol. 3, No. 1–2 (1988). 106–121.

McKay, Alex. (ed), Pilgrimage in Tibet. Surrey: Curzon Press, 1998.

Mitchell, W.J.T. Picture Theory. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1994.

Paniker, Ayyappa K. Indian Narratology. New Delhi: IGNCA, 2003.

Pimenta, Sherline and Ravi Poovaiah. “On Defining Visual Narratives.” Design Thoughts, IDC, Bombay, IIT, 2010.

Rajewsky, Irina O. “Intermediality, Intertextuality and Remediation.” Intermediality: History and Theory of the Arts, Literature and Technologies, No. 6 (2005).

Roerich, Georgesde. “The Ceremony of Breaking the Stone.” Journal of Urusvati Himalayan Research Institute of the Roerich Museum, Vol. 2, No. 4. 25–52.

Satyanath, T.S. “Processes and Models of Translation: Cases from Medieval Kannada Literature.” Translation Today, Vol. 2, No. 1–2. (2006).

Satyanath, T.S. “Mapping Transmediality in Medieval Indian Writing Culture: Formalistic and Social Epistemologies.” Indian Multilingualism and Language Behaviour: A Festschrift for Prof. H. M. Maheshwaraiah, ed. by Manjulakshi, L and M. Mahendra. Dharwad: Neelaparvat Prakashana. 72-84, 2020.

Sharma, Shivkumar. The Indian Painted Scrolls. Varanasi: Kala Prakashan, 1993.

Sharma, Shivkumar. Painted Scrolls of Asia. New Delhi: Intellectual Publishing House, 1994.

“Sita’s Ramayana.” Tara Books, tarabooks.com/shop/sitas-ramayana/. Accessed 1 Feb. 2023.

Skelton, Robert. “The Portrait in Early India.” The Indian Portrait: 1560-1860. Ahmedabad: Mapin Publishing Pvt. Ltd., 2010.

Smith, J.D. The Epic of Pabuji. New Delhi: Katha Publications, 2005.

Tucci, Guiseppe, Tibetan Painted Scrolls. 2 Vols. Rome: Libreriadello Stato. 1949.

Waddell, L.A. The Buddhism of Tibet or Lamaism. Cambridge: W. Heffer & Sons Ltd, 1958.

Wolf, Werner, and Walter Bernhart. Framing Borders in Literature and Other Media. Rodopi, 2006.

Wolf, Werner. “(Inter)mediality and the Study of Literature.” CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture, Vol. 13, No.3 (2011), <https://doi.org/10.7771/1481-4374.1789>, accessed 26th June 2021.

Zepetnek, Steven Tötösy de. “The New Humanities: The Intercultural, the Comparative, and the Interdisciplinary.” The Global South, Vol. 1, No. 2 (2007). 45–68.

Download PDF