1. Introduction

Roman Jakobson describes three methods of translating a verbal code. The first one is “intralingual” that is translation within the language such as rewording, interpretation and commentary. The second one is “interlingual” or translation from one language to another. He further states that there is no such thing as absolute synonymy in both methods, but they can be applied with the help of meta-language or borrowings. The third way of rendition is “intersemiotic” translation that could also be called transmutation. Jakobson further reiterates that there is a problem of equivalence in these three translation methods, as some information can be difficult to render when a target language has different grammatical categories from the source language. However, he simultaneously adds that any cognitive experience can be expressed in any language. We need to note that Jakobson not only presenting complex dependencies between linguistics and translation, but also points out the importance of the verbal code. There is a need for clarification here. Intersemiotic translation is an interpretation of verbal signs by means of signs from non-verbal sign systems (or vice versa). What has been discussed as intermediality in recent days is closely linked to the concept of intersemiotic translation. Though intermedial studies developed within the discipline of comparative literature to start with, subsequently in the American school of comparative literature it assumed the term inter-art studies while in Germany and Nordic countries it developed as part of media studies. The term intermediality was used by Aage Ansgar Hansen-Love as a terminological extension to Kristeva’s term “intertextuality,” which itself was inspired by Bakhtin’s concept of ‘dialogue’. It attempted to suggest the interconnectedness at thematic and formalistic levels, deriving readings not just from a text per se but from the interconnectedness to other texts. Similar to intertextuality, which contests authorial and textual uniqueness and deconstructs a text’s autonomy and independence, intermediality too incorporates these ideas and extends further into the domain of interdisciplinarity. In fact, Kristeva emphasised that it is not just texts, but all signs are defined and understood in relation to other signs. It is in this sense that Hansen-Love was able to connect sign systems with media. Accordingly, intermediality has become one of the important turns of the twentieth century, similar to cultural, linguistic and spatial turns. Intermediality has also tried to shift the emphasis from textuality in a narrow sense to representations in general and to the public sphere, whether it is reading or performing. A fruitful theoretical frame for the promotion of interdisciplinary cross-fertilisation is intermediality theory, in particular the category of intermediality as developed by scholars like Rajewsky, Wolf (2005, 2011), and Kattenbelt.

2. Formalistic and Social Epistemologies of Intermediality

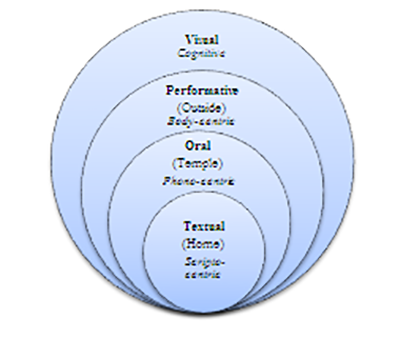

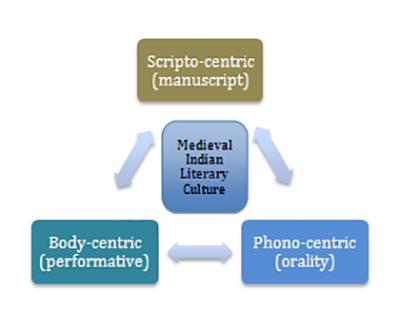

The theoretical formulation of intermediality, like literary theory, was essentially developed in the west and was extended to non-western cultures. As this mode of understanding literature has been there for more than 100 years and as attempts to look at intermediality from the point of view of Indian poetics are practically absent, there is an urgent need to initiate such studies. The attempt should bring formalistic and social epistemologies together in the study of intermediality. Rather than using a binary categorisation of textual and visual, we can use textuality, sonority, and visuality as the categories and designate them as scripto-centric (manuscript), phono-centric (orality) and body-centric (performative) systems of representation. Accordingly, at the construction and sustenance levels, we can notice that not only scripto-centric, phono-centric and body-centric representations overlap with each other (see Figure 1), but also the social epistemology gets fused into each other’s representational formats. The very fact that caste, gharana (family, lineage), spatiality (language and region), religion and ecological aspects like season, time of the day, etc. get firmly embedded in the construction of intermediality in Indian representations, the need to study the social epistemology of intermediality gets underscored. In addition, the linguistic, musical and performative aspects of intermediality are not all that uniform at universal levels as has been claimed. Discussions on print and translation claim advantages of easy linguistic transfer and larger universal isogloss of communication for print culture. But oral and performative formats, loaded with social epistemologies, may not be all that universal. Not only are musical and performative isoglosses relatively smaller, but also mutual compatibility between any two nonlinguistic mediums is relatively small. Moreover, the print mode-centred translation, the print public sphere, the formalistic cleavage, and the dominance of literary theory and translation studies have constrained intermediality on the one hand and interdisciplinarity on the other. At the same time, due to lack of interest and the complexity involved in studying them, intermedial studies have largely remained within the periphery.

A.K. Ramanujan provided seminal insights into the study of translation process in medieval India. Though the concept of translation in the sense that European theories postulate is conspicuously absent in medieval India, Ramanujan designates an indexical relationship between the purported ‘original’ and its translations and calls them “tellings.” In addition, he further reiterates that tellings constitute a creative crystallisation of conventions from a pool of signifiers available in the culture. Although Ramanujan does not make any mention of orality and performance representations or intermediality, tellings do encompass an overlapping relationship between scripto-centric, phono-centric and body-centric formats of representation. In fact, the conventions of signifiers could not only come from classical, popular and folk traditions but also could be consumed differently by different publics in multiple ways. Furthermore, the nature of the divide between the classical (elite) and folk was radically different from the binary opposition that has been conceived within contemporary discourse. Sarangadeva’s Sangita-ratnakara, an early canonical text composed in 1230 C.E. on Indian music mentions both elite and folk styles, Marga and Desi, and treats them as complementary to each other. The continuous and mutual exchange between Marga and Desi is well known and does not require a detailed discussion.

In order to map intermediality in medieval Indian literary culture, we need to take a closer look at how the literary culture and its publics operated and their social epistemologies. The general schema of precolonial representations included an overlapping of scripto-centric, phono-centric and body-centric systems of representation, each of them having a public of its own (roughly corresponding to home, temple and outside) with complex overlapping. However, during the colonial period, they were restructured into two-way spheres, “print” and “visual,” and a canonical and academic oriented approach of understanding them was developed. Such changes had far-reaching consequences for precolonial schema of the representation system and its publics. First, print and visual cultures were linked to two newly emerging public spheres that had emerged as a consequence of the new educational system. Consequently, the three-fold, hybrid and overlapping precolonial publics, the court, temple and outside, which were still actively present, were marginalised and denigrated. Secondly, hybridity associated with the precolonial representation system was intended to cater to the needs of heterogeneous and divergent communities that were a characteristic of pre-colonial publics. In contrast, the newly emerged print public sphere was one of not only literates but was also homogeneous and convergent in nature. Let us take a look at an example of medieval Indian literary work (Kavya) in different public spaces, namely the home, the temple and outside and the incorporated intermediality to understand how despite being composed in the scripto-centric manuscript format, it was consumed.

In medieval Indian literary culture, texts are divided into Parvas/Kandas, which are further divided into subdivisions, namely Sandhis (joints). It is actually Sandhi in the form of an episode that is usually recited or performed or sculpted/ painted in representations. Thus, Sandhis forms the smallest modular unit of the Kavya system. These modular stories are arranged in different patterns to constitute a Kavya. In the domain of the home, the text is usually read aloud to oneself or in front of the family members after worship in the morning. In phono-centric (recitation) system it transforms into Kavya–vachana (Gamaka–vachana, recitation of Kavya to tune of Ragas) that usually takes place in temples in which a chosen episode from a text is sung to the tune of Ragas of classical music and interpreted by the singer himself for an expert interpreter. Such recitations usually start with introductory and invocatory verses of the Kavya, followed by the synoptic verse (Sucana–padya) and then the entire episode and conclude with verses of Mangala (well-being) and Phalashruti (benefits). The people from castes who are customarily allowed to enter the temple have the potential to become its audience. Thus, as the temple public becomes diversified (from home to temple), interpretation strategies are improved to cater to the needs of the sensibilities of the changed public. Interestingly, body–centric systems too contain a similar synoptic verse that is narrated at the beginning of the performance and follow a pattern similar to that of phono-centric system. In this case, the text moves into open space (Bayalu, “open field;” Bayalata, “folk-play”) and as anyone can become its audience, further diversification of its public space takes place[1] Accordingly, in addition to the music and costume, acting and dialogues get incorporated to enhance the process of interpretation. On the other hand, sculptural and painted representations of episodes from the Kavyas, located on the exterior walls and pillars of the temple and depicted at a human vision level, provide certain key narrative visual elements that are representative of the episode on which the viewers can mentally rebuild the episode for themselves. In a sense, these key narrative visual elements constitute the counterpart of the synoptic verse for sculpture and painting. However, in the absence of scripted and verbal texts, it is the viewer’s mental text(s), through a dense intertextuality (knowledge of multiple versions and their social epistemologies), that facilitates a mental reading of the episode. This process is closer to the aesthetic experience discussed in Indian poetics, the Rasanubhava.

Kavya–vachana performances usually start with Raga Nata and conclude with Madhyamavati or Suruti in Karnataki style of music and with Raga Yaman Kalyan and Bhairavi respectively in Hindustani style. Interestingly, the performance starts with a late evening Raga and ends with an early morning Raga suggesting the performance was conceived as a dusk to dawn activity. In most of the Indian languages, folk plays, Kirtan, Jagaran, Qawwali, etc. are performed through the use of this convention. Thus, Ragasbring forward important and crucial social epistemology to the temporal and thematic development of the narrative, whether it is being read, sung, or performed. At the same time having a potential for highly diverse public sensibilities, the body-centric system tends to possess a very complex intermedial format involving text, music, dance, costume, etc. Thus, while the phono-centric system subsumes the scripto-centric system, the body-centric system subsumes both phono-centric and scripto-centric systems. With regard to the overlapping of scripto-centric, phono-centric and body-centric systems, it can be safely assumed that their reach is directly proportional to the diversity of the publics in which they are located. A scripto-centric system’s reach subsumes literacy, while a phono-centric system is devoid of such a literacy constraint. However, dialectal and linguistic boundaries might act as constraints for its efficacy, but bi-dialectal and multilingual capabilities of the publics might help an easy negotiation of such constraints. On the other hand, a phono-centric system has to incorporate elaborate interpretative mechanisms into its format to cater to the diverse sensibilities of its pubic on the one hand and to facilitate the understanding of the archaic languages of the text on the other. However, a body-centric system with a public of a high degree of diverse sensibilities tends to become a complex intermedial representation involving text, music, dance, costume, etc. Sculptural and painted representations, on the other hand, operate at a cognitive/mental level of the viewers. Having a set of limited clues, they allow the viewer to imagine and create an intertexuality with the viewer’s cultural repertoire about the episode narrated in the representation. As we move away from the scripto-centric system and go to the phono-centric and further into body-centric systems, we are in fact increasingly encountering social epistemology associated with caste, gender, religion etc., as these categories not only constitute the monopolistic archives of knowledge about the respective systems but are also the custodians of knowledge of music, theatre, sculpture, and painting. At the construction and sustenance levels, we can further notice that not only scripto-centric, phono-centric and body-centric representations overlap with one another, but also the social epistemologies get fused into artistic representations. More importantly, while print culture has brought in significant changes in the literary forms in Europe, several medieval Indian intermedial forms are still alive and continue to exist within the print public sphere. Figure 1 schematically shows the isoglosses of these overlapping medieval intermedial publics.[2]

The above discussion and the figure, however, may appear to privilege scripto-centric system to be the primary system, and the phono-centric and body-centric systems to be its derivatives. But the reality is contrary to it and needs to be problematised further. There are several instances of Indian narratives in which the phono-centric and body-centric representations take a radically different thematic pattern compared to their scripto-centric counterparts. In certain cases, the body-centric versions might predate the scripto-centric versions. The episode of Kirata Shiva and Arjuna, fighting for a wild boar, from the Mahabharata is an interesting example of this kind. Scholars think that this episode is an interpolation into the text. Interestingly, the sculptural version pre-dates the textual version, the earliest version being reported from a panel from Virupaksha temple, Pattadakal dating back to 740 C.E. Above all, the version of the episode represented in the panel is different from the version that we find in the Sanskrit versions of the Mahabharata of Vyasa and Kiratarjuniyam of Bharavi. In fact, this deviant version of the episode continues to be in currency not only in the sculptural and painted versions but also in vernacular (c.f., Pampa’s Vikramarjuna–vijayam in Kannada, 932 C.E.) and oral versions up to the nineteenth century.[3] Similarly, many stories from Panchatantra differ from their literary counterparts. Patil has pointed out that the sculptural versions not only differ from the literary versions but also predate the literary versions, both in India and in Indonesia. All these suggest that scripto-centric, phono-centric and body-centric representational systems have their own formalistic and social epistemologies that are specific to their respective publics and though they keep overlapping to a certain degree, they also remain autonomous to some extent. Figure 2 schematically suggests the dependent and autonomous aspects of scripto-centric, phono-centric and body centric systems in medieval Indian literary culture.

3. Ragamala Painting as Intermedial Representation and its Social Epistemology

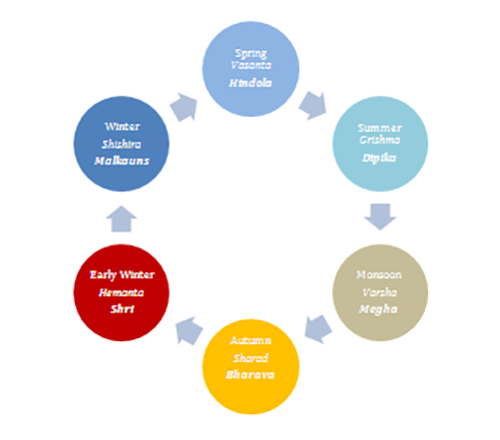

Any discussion of Indian intermediality is incomplete without bringing Ragamala paintings into focus. The genre called Ragamala paintings literally means a garland of Ragas, or musical melodies. It is a case of perfect intermediality of medieval Indian literary culture involving scripto-centric, phono-centric and body-centric systems within an elite public. Raga refers to a “musical composition or mode,” and each Raga has its temporal dimension as to which time of the day it should be sung (daily cycle) and also seasonal association (annual cycle) and its own presiding deity. While the first cycle subsumes temporality, the second one subsumes ecological and spatial dimensions. Accordingly, from the ecological perspective, the six-way calibration of seasons in India, spring (Vasanta), summer (Grishma), monsoon (Varsha), autumn (Sharad), early winter (Hemanta) and winter (Shishira), corresponds to the six ragas Hindola, Dipaka, Megha, Bhairava, Shri and Malkouns respectively. In addition, they also have their respective presiding deity, mood, flora and fauna, heptatonic scale etc.[4] Figure 3 schematically shows the seasons and the Ragasassociated with them. In fact, they resemble the ecocentric types like Tinais(poetical modes) of Sangam literature in Tamil. While the Sangam modes are landscapes, the musical modes are seasons.

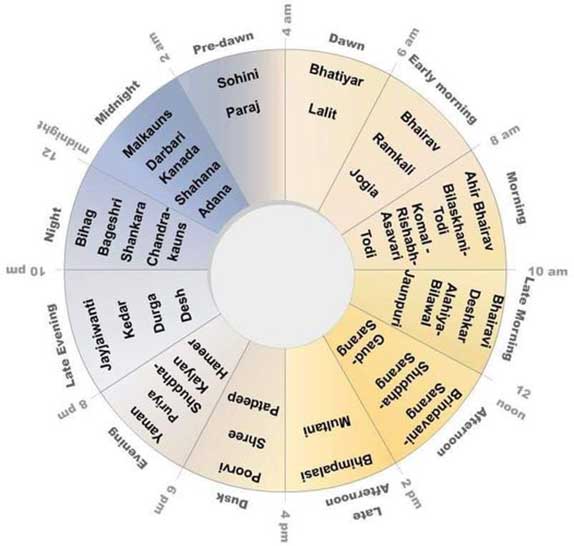

The daily time cycles of various Ragas are shown in Figure 4.[5] The schema in the figure accounts for thirty-nine Ragas. The total number of Ragas, be it in Hindustani or Karnataki style, is a matter of debate, and different canonical texts list the numbers as well as names of the Ragas differently. In addition, these seasonal and temporal prescriptions are only heuristic devices and are not rigidly followed in practice.

The folio format in which the Ragamala has been put together suggests a thematic exposition of Ragas in terms of a family and usually constitutes 36 or 42 folios in a ledger. At one level, Ragas have been conceived as a family with a male Raga as the head of the family and having wives (Raga–patnis) and sons (Raga–putras). For example, Raga Bhairava (male) has been claimed to have five wives and eight sons. According to Sangita–darpana of Damodara, Bhairavi, Bilawali, Punyaki, Bangli and Aslekhi are Bhairava’s wives. In Mesakarna’s schema, Pancham, Harakh, Disakh, Bangal, Madhu, Madhava, Lalit and Bilaval are his sons.[6] The number of Ragas continues to grow after the 16th century. However, both temporal and ecological clues get represented in the paintings. At another level, stylistically and medium wise, Ragamala paintings appear to be a spinoff from Persian miniature paintings. However, they appear to have successfully localised the conventions to suit the sensibilities and tastes of the local public. In addition to the depiction of local flora and fauna, that provide visual clues, “Dhyana” or “Dhyana–shloka” (contemplation), a verse either in Sanskrit or Braj, is inscribed either in Devanagari, or Naqsh, or Telugu script for verbal clues. This scripto-centric part of Ragamala painting, though confined to a small strip at the top of the painting provides hints to the viewer to understand the painting and its accompanying music. There are also instances where the verse may be absent, suggesting the absence of scripto-centric counterpart in the painting. As the Ragas subsume a presiding deity of the Hindu pantheon, an iconographic representation of the presiding deity could also be found in the painting.

Historically speaking, Ragamala paintings appeared several centuries after the classification of Ragas appeared in the canonical texts on music. A musical treatise from western India, Sangitaopanishat–saroddhara written in 1324 C.E. by a Jain philosopher Sudhakalasha, provides highly valuable information regarding the Dhyana–shlokas and contains the first pictorial descriptions of the Ragas anticipating the later Raga–dhyanas and the painting that could be found subsequently on the folios of Jain Kalpasutra manuscript of Jayasimhasuriji of Indore. Ebiling suggests that the Ragamala paintings probably came into existence around 1450–1550 C.E. The depiction of six multiarmed male deities, labeled as Raga, and thirty-six female figures as Ragini on the back of twelve Jain Kalpasutra folios from Gujarat, dateable to 1475 C.E. are the earliest specimens of Ragamala paintings that have survived. These Jain connections, both to textual and painting traditions, deserve further research.

Deccan is one of the regions from which Ragamala paintings have been reported extensively. Zebrowski observed that probably the earliest Ragamala paintings were executed in Ahmednagar during the period 1580–1600 C.E. Thus, the spatial distribution of Ragamala paintings is spread over royal and Muslim courts from the regions of Deccan and North-Central India and is differentiated by various regional schools. It has also been observed that a majority of the extant Ragamala paintings that have been reported are found to be either in Deccani style or mixed with it. At the same time, there is a conspicuous absence of Ragamala paintings from the region in which the Karnataki style of music has its dominant presence. Accordingly, no Ragamala painting has been reported from South India. This suggests that it is North India and Deccan that have shown keen interest in this music-centred intermedial representation form. Furthermore, the association of Ragas with seasonal and temporal considerations is not all that well defined in the Karnataki style of music. Interestingly, though the story of music in India is traced back to the Vedas, and Matanga’s Brihaddeshi (6th–8th century C.E.) is the first text to talk about Ragas, the earliest definitive canonical text is actually Sarangadeva’s Sangita-ratnakara, composed in 1230 C.E. in Devagiri in Deccan. The text is composed in Sanskrit and applies equally well both for Hindustani and Karnataki styles of music. Another noteworthy aspect of Ragamala paintings is that they visibly carry features associated with Hinduism, both in terms of people present in paintings and deities. In addition, more and more women could be seen represented in the paintings compared to men. Despite all this, Ragamala paintings need to be understood as a part of Hindu–Muslim syncretic tradition, as not only both Hindu and Muslim painters painted them, but also due to elements of Indo-Saracenic architectural style on the structures in the paintings.

A variety of hybridity has gone into the construction of Ragamala paintings. While the use of paper, the technique of miniature, architectural details, floral design and the names of some of the painters point towards a Persian origin, several other details like the colours, iconography and musical conventions come from the local cultural world. There are also suggestions that by the 15th century Indian music underwent changes to accommodate Persian elements. Ramamatya’s Svara-mela-kalanidhi, written in the Vijayanagara court in 1550 C.E. has been claimed to have accommodated aspects of Persian music. Similarly, the occurrence of the term Raka in Persian has been suggested to be a contribution from Indian music.

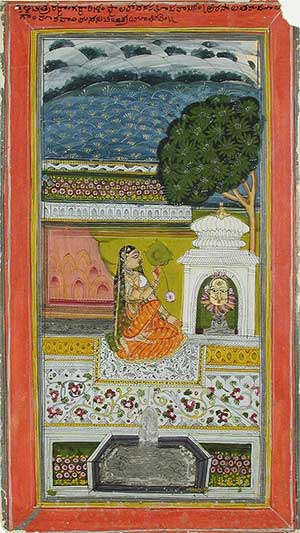

In order to understand the nature and intricacies of Ragamala paintings, let us take a closer look at some of the paintings. For the sake of uniformity, I have chosen instances of Ragini Bhairavi for discussion. Figure 5 gives a Ragamala painting of Ragini Bhairavi from the Manley Ragamala album, an album of paintings in gouache on paper now preserved in the British Museum.[7] It is originally from Amber, Jaipur (Rajasthan) and was executed during 1610–20 C.E. The painting depicts a woman (Gouri) worshipping a Shiva–Linga along with an accompanying female worshipper, probably an attendant. While the worshipper looks like singing in praise of Shiva with cymbals (Tala) in her hands, the attendant is helping her, fetching a garland in her hands. The worshipper sits in a pavilion of crystal, amidst a lake, which is filled with lotuses and water birds. At the base of the Linga are various ritual vessels, while a minuscule bull, the vehicle of Shiva, is shown curled up on the steps of the pavilion.[8] There is a Dhyana Shloka in Sanskrit written in Devanagari script which could be read as follows:[9]

sarovrasthā sphtiksya-maṃḍape saroruhai sankaram-arcayaṃtī

tala-pratobhedai pratipanna-gītaiḥ gorī suciṃ nārada-bhairavīyaṃ

This verse could be roughly translated as follows:

In a crystal pavilion located amidst a pond, Gouri, bathed and clean, is

worshipping Shankara, singing Narada Bhairavi [10] to different beats.

It is a problematic issue that no Ragamala painting has been reported from South India that constitutes the region of Karnataki style of music. The southernmost point in Deccan from which Ragamala painting has been reported is from Wanaparthy in Karnool district of Telangana, executed in 1755 C.E., under the patronage of a local Hindu feudal lord.[11] The painting can be seen in Figure 6.

What is interesting about this painting is that Dhyana Shloka is in Jagati metre, a Vedic meter, and in Telugu-Kannada script.[12] The verse is as follows:

kēļī citra rathāṃga-dhariṇīṃ

phāla-lōchana samīpa vāsainīṃ

arasāla-tarumūla (vāsa)nāṃ

mārav(ḥa)ṃ manasi-ciṃtayāmiyēṃ

A tentative translation of the verse is as follows:

Holding various armours in different postures,

in proximity to the one who has an eye on his forehead,

living under a mango tree,

is the goddess who excels as the god of love, Mara, I think of her.

It is not necessary that all Ragamala paintings should necessarily have Dhyana Shlokas in them. Sometimes there may be mention of only the name of the Raga and sometimes there may not be anything mentioned at all. This suggests that the phono-centric and body-centric components of Ragamala paintings are more important than the scripto-centric counterpart. Let us look at some of the Ragamala paintings in which Braj has been used. In these cases, the Dhyana Shlokas could be found in metres such as Doha (two-line meter) and Chaupai and Savaiya (both are four-line meters). Chandra (92) discusses a Ragamala painting of Ragini Bhairavi in Rajasthani style from the late 16th or early 17th century.[13] The following Doha verse is on the painting:

ānandita saṃjoga-sira siva devani ke deva

mānasarovara tīra taki karati bhairavi seva.

rāganī bhairavī bhairo kī dohā

The translation of the verse is as follows:

Delighted by the vision of her union with Shiva the god of gods,

Bhairavi attends upon him on the banks of the Manasa Lake.

Ragini Bhairavi of Bhairava

Another painting of Ragini Bhairavi in Rajasthani style from Jaipur and executed in the 17th century C.E. has two Dhyana Shlokas, a Chaupai and a Doha (Chandra 93-94).[14] The two verses are as follows:

bhairavī rāganī copaī

rājakuvāri bhairavī rāṇī, deśī-rupa bhairau lalicāṇī

bhāi magna sava surati visārīt rāṣi manoratha śiva matha āī

vauhauta bhāti kai pūjā lāī

līyai tāla kara sujasa sunāvā mana ehīva bhairava pāvā

eha nimata iota gāḍu ḍhārai pīya saneha nahī naika visārai

Doha: mānasarovara vimala jala panṣī karata kilola

tihā taṭa sobhī siva bhavaṇa rājita rucita amola

The translation of the two verses is as follows:

Princess Bhairavi was tempted by the sight of Bhairava’s beauty.

Becoming absorbed (in his love), she forgot everything

and came to the temple of Shiva with a vow in her heart,

and brought with her many articles of worship.

Holding the cymbals in her hands she is singing the glories of Bhairava,

believing all the time that she had secured him.

With this purpose she is pouring out water from the pitcher

and does not forget even for a moment the love of her beloved.

Doha: On the banks of the Manasa Lake, full of crystalline water,

where the birds are sporting, is situated the ornamented and priceless

temple of Shiva.

There is another Ragamala painting of Ragini Bhairavi, once again in Rajasthani style, from Jaipur and belonging to the 19th century. (Chandra 96-97).[15] The Dhyana Shloka here is in the Savaiya metre.

bhairvā kī rāga savayā

phūle jahā puṇḍarīka indīvara aise sarovara madhya suhāvai

sundara rūpa singāra kiyai yaha gāvata tāla vajāvata bhāvai

prema sau dhyāna dharai śiva kau, phalase kuca nākita hātha lagāvai

yā vidhi bhāva vaṣāniye bhaironkī, rāginī bhairavī nāma kahāvai

The translation is as follows:

(The temple) is beautifully situated in a pond full of water lilies and

lotus blossoms.

She, having decorated her beautiful person, appears there singing

melodiously and beating time.

Meditating upon Shiva with love, she touches her fruit-like breast with

her hand.

This is the attitude of the Ragini of Bhairava known as Bhairavi.

The common features that we notice in the Dhyana Shlokas like the reference to Manasa Lake, the lotus blossoms, music, and musical instruments create a pool of conventions intermedially, both in words and visually. The conventions described in the verse could also be found in the paintings to a considerable degree. In fact, the lake, lotus blossoms, shrine, musical instruments, devotees, dawn and the bluish sky and trees are common in about thirty-one Ragamala paintings of Ragini Bhairavi that are there in my archive. To understand the significance of the relation between textual and visual representations, let us take a look at the trees that appear in these paintings. The mango tree and banana plant constitute an integral part of Ragamala paintings of Ragini Bhairavi and let us look at the cultural significance of the mango tree to understand the social epistemology of its representation in the paintings.

The depiction of a mango tree, sometimes blooming with flowers, suggests spring, when the Ragini is to be sung. Although the painting in Figure 5 does not show a mango tree, a blooming mango tree could be clearly seen in Figure 6. In a majority of the 31 paintings that I have seen a mango tree has been depicted. Interestingly, the Sthalapurana in Kanchipuram in Tamil Nadu states that the name of the presiding deity, Ekambareshvara, signifies the Lord of the mango tree. Another version of the Sthalapurana says that Parvati, in order to expiate herself from a sin, performed penance under the mango tree located in the premises of the Ekambareshvara temple on the bank of the river Vegavati. There is a song composed in Sanskrit by the famous composer of the Karnataki style of music Muthuswami Dikshitar (1775-1835) in Raga Bhairavi which refers to the Mango tree as the abode of Shiva and Uma.

cintayama kaṃda mula kandaṃ

cetaḥ śrī somaskandaṃ

The translation of the verse is as follows:

O mind, meditate on the root (or the origin of everything) at the base of

the mango tree, where Shiva is in the company of Uma and Skanda.

Hence, the mango tree brings in mythological, seasonal, and temporal dimensions into the text, music and visuality of Ragamala painting of Ragini Bhairavi. Temporally speaking, though Ragini Bhairavi is claimed as the Raga meant for singing during the autumn (Sharat) season in canonical texts, it could also be sung during other seasons. However, its usual singing time is at dawn. Although the darker sky represented in several paintings suggests that it is either predawn or dawn, the time-cycle given in Figure 3 suggests a late morning time for Ragini Bhairavi. Such mismatches are common in the conventions of Indian music which overwrites practice over canon.

Dawn and the singing of Ragini Bhairavi have interesting intertextuality with Indian poetics. In Sanskrit and vernacular poetic traditions, Suryodaya-varnanam, the description of sunrise, is considered as one of the eighteen descriptions essential for a Mahakavya. The conventions date back to the time of Kavyadarsha by Dandin. In this regard Ragini Bhairavi itself could be explored as a connecting link between the medieval Indian cosmopolitan literary culture, music and Ragamala paintings. In order to understand the cultural significance of such a link, I would like to take up a comparison between Suryodaya-varnanam (the description of sunrise) from medieval Kavya literature, a song from Sangīta Saubhadra, a Marathi Sangit Natak (musical play) written by Annasahab Kirlosker in 1882, and the Ragamala painting of Ragini Bhairavi.

Suktisudharnavam by Mallikarjuna, a Kannada Jaina poet (1350 C.E.), is an anthology of poems of eighteen descriptions in which each canto provides examples of poems of a specific description. The synoptic verse 9.1 (Sucana-padya) of the ninth canto, Suryodaya-varnanam, prescribes the following constituents for the description of sunrise:

(1) Water lilly (kumudaṃ), (2) fish (mīn), (3) setting of the moon / fading moonlight (candramaṃ-candrikeya-kaļeyarataṃ), (4) gradual dimming of lamps (jyōtinasyaṃ), nayaguṃde manaṃ pankhēruhaṃ (5) cool early morning breeze (taṇṇelar), (6) brightness of the dawn (avasara-tūryaṃ), (7) chariot (rathāṃga-dvayaṃ), (8) dawn’s light (sāndhya-mayūkhaṃ), (9) increasing of mist (perce marbuṃ), (10) early morning sleep (susila-marapu), (11) birds’ twitter (pakṣi-svanaṃ), (12) Ragini Bhairavī (bhairavi-rāgumgurvaṃ bīre) and (13) movement of people (pānthar-naḍeye).

The prescriptions for sunrise given in this 14th century text that is remarkably in agreement to the description of sunrise in the song Priye-paha from the modern Marathi musical play, Sangita Saubhadra. However, instead of Bhairavi, Ragas Deshkar and Bhoop have been used.[16] In the link given below, we can listen to the song sung by renowned singer Prabhakar Karekar. The lyrics of the song and translation are given below:[17]

priye paha ratrica samaya saruni yeta ushah kaal ha

thanda gar vata sutata dipa teja manda hota

digvadane svachcha karita aruna pasari nija maha

pakshi madhura shabda kariti gunjrava madhupa variti

virala parna shakhi hoti vikasana ye jalaruha

sukhdukha visarunia gele je vishva laya

sthiti nija tee sevaya uthte ki techi aha

The translation is given below:

Behold my dear beloved, look the aura arrives on the horizon, night has

gone.

She comes hither, cold wind of early morning, night lamps loose burn slowly.

The sun spreads lustre, clearing faces of direction

Birds chirp sweetly, bees hover on sweet nectar.

The leaves are withering revealing the branches, the lotus is blooming.

Water haunts get enriched, world that has forgotten

Sorrows and worries in sleep.

What is striking is the astonishing agreement between prescriptions from medieval canon of poetics and the nineteenth century modern musical play. This demonstrates astonishing continuities not only across time but also across genres, like the elite cosmopolitan and vernacular conventions of Kavya, nineteenth century modern theatre and Ragamala paintings. Table 1 shows that seven out of thirteen prescriptions for sunrise from Suktisudharnavam have been maintained intact in Priye–paha from Sangita Saubhadra. The canonisation of music and literary canons was yet to crystallise when this play was written in 1882 and Ragamala paintings were virtually unknown to the scholarly world.

Table 1. Table Showing the similarity of details in the description of sunrise in the Kannada Text Suktisudharnavam and the Marathi play Sangita Saubhadra

| No | Description: English | Suktisudharnavam (Kannada) | Priye-paha (Marathi) |

| 1 | Lotus | kumudaṃ | vikasana ye jalaruha |

| 2 | Fish | mīn | – |

| 3 | Fading moonlight | candramaṃ-candrikeya-kaļeyarataṃ | – |

| 4 | Dimming of lamps | jyōtinasyaṃ | dipa teja manda hota |

| 5 | Cool morning breeze | taṇṇelar | thanda gara vata sutata |

| 6 | Brightness of the dawn | avasara-tūryaṃ | aruna pasari |

| 7 | Chariot | rathāṃga-dvayaṃ | – |

| 8 | Dawn’s light | saṃdhyā-mayūkhaṃ | – |

| 9 | Disappearance of mist | marbuṃ | – |

| 10 | Early morning sleep | susila–marapu | uthte ki techi aha |

| 11 | Birds’ twitter | pakṣi–svanaṃ | pakshi madhura shabda karici |

| 12 | Ragini Bhairavī | bhairavi-rāgamuṃ | Deshkar and Bhoop |

| 13 | Movement of people | pānthar-naḍeye | – |

Despite the temporal continuities we noticed above, there are innovative changes that keep occurring and make performative traditions a continually evolving system. To demonstrate this point, let us take a look at one of the video versions of Priye–paha.[18] The context of the song is as follows: Krishna and Rukmini have been having an argument all night, and Krishna attempts to put an end to it by singing the song. In Indian plays and cinema songs signify shift in moods and are highly stylised in nature. The song starts after 2.43.4 and when Krishna sings the line “thanda gara vata sutata” he takes a shawl in his hand and puts it around Rukmini’s shoulder gently. This suddenly transforms the mood of argument into a romantic one. There are six different videos of this song by different troupes on YouTube and each one of them has done the sequence differently. However, the issue of innovation brings to the forefront the point that while textuality is a relatively static component, the performative components, music, costume, dialogue, proximics and kinesics, are not only fluid but also dynamic in nature and help in transforming intermediality to a continually creative and innovative system.

In a different sense, the continuity we noticed above demonstrates not only the continuity of knowledge about literary conventions, but also intermediality and the overlapping of literary, musical, and painting systems. For instance, the reference to the lotus pond (implying the sacred Manasa Lake of Kailasa) with blooming lotuses in it and the use of lotus for worshiping Shiva in Dhyana Shlokas, paintings and theatre song is a remarkable continuity in medieval Indian knowledge system. It also demonstrates that intermediality need not necessarily depend on textual sources for its sustenance and transmission. These correspondences clearly establish a complex hybridity between scripto-centric, phono-centric and body-centric systems on the one hand and the role of social epistemology in sustaining the system.

4. Musicological Canon, Ragmala Paintings and Bhakti Compositions

Similar to Ragamala paintings that created intermediality between scripto-centric, phono-centric and body-centric representations, is the case of Bhakti movements in Indian languages. The components of Bhakti were constructed by making use of a variety of materials, Marga and Desi; Sanskritic, vernacular, folk and tribal; classical, popular, and folk and most importantly intermediality. Hence there is a need to take a closer look at Bhakti and its intermediality. In the past two hundred years, Bhakti studies have been essentially textual studies. An attempt to decentre the textual bias and to advocate using music and performance to study Bhakti has been undertaken here.

The time of onset of Bhakti compositions in Indian languages is not uniform across languages. Bhakti compositions in Tamil started in the 5th century, 12th century in Kannada and Telugu, 13th century in Marathi and 14th century in Assamese and Malayalam, and 15th century in other languages. However, there is a gap of three to four centuries between the time of composition and its canonisation. In some cases, the process of canonisation started only after attempts were made to put them into the print format during the 19th century. While it is in the 10th century the Tamil Shaivite Tevarams were codified and put into a manuscript format, the Kannada Virashaiva Vachanas were codified and put into a manuscript format in the 15th century. While in the case of Purandaradasa in Kannada, Mira in Hindi and Lal Ded in Kashmiri, their compositions remained in oral tradition till attempts were made to print them in the 19th century. All along the medieval period, these compositions were sustained by singers and performers, belonging to specific singing and performing castes, many of them itinerary professional groups. Several Bhakti sects consider pilgrimage to the locations of temples of the sectarian deity as an essential part of worship. Such pilgrimages facilitated the singers and devotees to travel together singing and performing Bhakti compositions. Warkari, Nama–sankirtan, etc. are some of the itinerary activities that involve singing and performing of Bhakti compositions. In fact, it is these itinerary castes and communities that have sustained Bhakti compositions in the absence of a scripto-centric (manuscript) tradition. This has not only brought in music and performance into Bhakti compositions, but also has transformed them into intermedial representations.

Bhakti compositions have been understood in the past two centuries essentially as printed texts, ignoring the publics in which they were produced and consumed. The established practice of understanding literary texts since the advent of colonial modernity is either as nationalistic (national literature) or regional (vernacular literature), sectarian (religious) or caste-based or as the creation of a poet. Such attempts tend to strip Bhakti not only from the social epistemology of caste, gender, tribe, etc. but also from intermediality. Bhakti’s dissemination in medieval Indian literary culture took place through singing and performing which are actually caste-specific knowledge systems. To understand Bhakti as a product of a performative public sphere, we need to go to its intermediality and the sensibilities of the performative public sphere. While women sang Bhakti poems along with their daily chores (prabhata, sandhya etc.) and seasonal activities (hori, savan etc.), the professional singers carried them into homes and folk plays.

In order to understand the complex relationship between Bhakti compositions, music, and performative traditions, I have tried to put together temporal and spatial aspects of canonical texts on music, Ragamala paintings of Ragini Bhairavi and the onset of Bhakti compositions in a comparative perspective. They together provide a distant reading of temporal and spatial aspects of the three representational formats in the form of three isoglosses.

Table 2 provides the temporal and spatial aspects of canonical texts on music. I have made use of Nijenhuis’s Musicological Literature to arrive at this table. It provides a distant reading of canon of Indian musicological texts from the 1st century C.E. to 18th century C.E. with fifty-seven texts, some of them translations of earlier texts and some commentaries. The region from which the texts have come provides the spatiality of their composition, although most of them were composed in royal courts and hence had a particular public to which they catered. It is interesting to note that a majority of these texts were composed in Deccan, South India, Central India and Western India, although during the post-17th century period we notice that they start appearing also in Eastern India. Curiously this order is also the historical sequence and spatiality of Bhakti movements within the subcontinent.

Table 2. Table showing the Temporal and Spatial Details of Canonical Texts on Music

| No | Time | Name | Author | Place |

| 1 | 1st cent. | Naradiya-shiksha | Narada | – |

| 2 | 8th cent. | Dattilam | – | – |

| 3 | 9th cent. | Brihaddeshi | Matanga | Vijayanagar |

| 4 | 12th cent. | Abhinaya-darpana | Nandikeshvara | |

| 5 | 1131 | Manasollasa | Someshvara | Kalyana, Deccan |

| 6 | 1140 | Sangita-chudamani | Jagadekamalla | Kalyana, Deccan |

| 7 | 1179 | Sangita-sudhakara | Haripala | Gujarat |

| 8 | 1199 | Gitalankara | Bharata | – |

| 9 | 12th cent. | Gitagovinda | Jayadeva | Mithila |

| 10 | 1210 | Bhava-prakasha | Sharadatanaya | – |

| 11 | 1230 | Sangita-ratnakara | Sarangadeva | Devagiri, Deccan Dhyana Shlokas |

| 12 | – | Sangita-samyasara | Parshvadeva | – |

| 13 | – | Sangita-makaranda | Narada | – |

| 14 | 1253 | Nritta-ratnavali | Jayasenapati | Warangal, Deccan |

| 15 | 14th cent. | Pancha-sara-sahita | Narada | – |

| 16 | 14th cent. | Sudhakara | Sihabhupala | Rajachala, Deccan |

| 17 | – | Nrityadhya | Ashokamalla | – |

| 18 | 1324 | Sangitopanishat | Sudhakalasha | Jain |

| 19 | 1350 | sangitopanishat-saroddhara | Sudhakalasha | Jain Ragamala painting |

| 20 | 1428 | Sangita-shiromani | – | Muslim Allahabad |

| 21 | 1450 | Kalanidhi (Com.) | Kallinatha | Vijayanagar |

| 22 | 1450 | Sangita-raja | Kumbha | Mewar |

| 23 | 1550 | Svara-mela-kalanidhi | Ramamatya | Vijayanagar |

| 24 | 1570 | Ragamala | Kshemakarna | – |

| 25 | 1575 | Rasa-kaumudi | Srikantha | Navanagara, Gujrat |

| 26 | 1576 | Raga-manjari | Pundarika Vitthala | Jaipur |

| 27 | 1576 | Ragamala | Pundarika Vitthala | Jaipur |

| 28 | 1580 | Sangita-damodara | Shubhankara | Bengal |

| 29 | 1580 | Hasta-uktavali | Shubhankara | Dance |

| 30 | 1580 | Sangraha-sara | Shubhankara | – |

| 31 | 14th/15th cent. | Sangita-makaranda | Narada | – |

| 32 | 1609 | Raga-vibodha | Somanatha | – |

| 33 | 1614 | Sangita-sudha | Govinda Dikshita | Tanjore, South India |

| 34 | 1620 | Chaturdandi-prakashika | Venkataakhin | Tanjore, South India |

| 35 | 1625 | Sangita-darpana | Damodara | DhyanaShlokas |

| 36 | – | Sangita-saroddhara | Haribhatta | Translation of Damodara |

| 37 | – | – | Harivallabha | Hindi Translation of Damodara |

| 38 | 16th -17th cent. | Chatvarimshacchta-raga-nirupana | Narada | – |

| 39 | 1650 | Abhinava-bharata-sarasangraha | Mummadi Chikkabhupala | Madhugiri, South India |

| 40 | 17th cent. | Sangita-parijata | Ahobala | Deccan, Persian tr. in 1724 |

| 41 | 1724 | ? | Dinanath | Translation of Pundarika Vithala |

| 42 | 17th cent. | Raga-tatva-vibodha | Srinivasa | Ahobalam (Deccan) |

| 43 | 1667 | Hridaya-prakasha | Hridayanarayana | Jabbalpur |

| 44 | 17th cent. | Ragatarangini | Lochana Kavi | Mithila |

| 45 | 17th cent. | – | Bhavabhatta | Bikaner |

| 46 | 1730 | Sangita-narayana | Purushottama Mishra | Parlakimidi (Deccan) |

| 47 | 1730 | Alankara-candrika | Purushottama Mishra | Parlakimidi (Deccan) |

| 48 | 18th cent. | Sangita-kaumudi | Sanasena | Oriya Translation |

| 49 | 18th cent. | Kalankura-nibandha | Kalankura | Oriya Translation of Damodara |

| 50 | 18th cent. | Gita-prakasha | Krishnadasa Mahapatra | Oriya Translation |

| 51 | 18th cent. | Sangita-sarani | Narayana | Orissa |

| 52 | 18th cent. | Shringara-chudamani | Govinda | – |

| 53 | 18th cent. | Sangita-kaumudi | Sanasena | Oriya Translation |

| 54 | 18th cent. | Sangita-sarani | Narayana | Orissa |

| 55 | 18th cent. | Shringara-chudamani | Govinda | |

| 56 | 18th cent. | Sangita-muktavali | Harchandana Bhanja | Orissa |

| 57 | 1730 | Sangita-saramitra | Tulaja | Tanjore, South India |

Table 3 provides the temporal and spatial distribution of Ragamala paintings of Ragini Bhairavi. As Ragamala paintings are not easily available, I have depended on the websites that have uploaded them for public use and there may be several paintings which are still not accessible for viewing. It is important to note that most of them were taken away to various parts of the world during the colonial period and have subsequently landed in museums. I have collected about 31 paintings of Ragini Bhairavi in the archive used here. Although the earliest available Ragamala Painting goes back to 1475 C.E. and the textual reference to it in the musical canon to a much earlier date, the earliest example of Ragini Bhairavi that I have in the archive is from 1520 C.E. A majority of these paintings actually come from Central India, Western India and Deccan in the order that has been mentioned. The temporal and spatial distribution of Ragamala paintings of Ragini Bhairavi further substantiates the point made with regard to canonical texts on music that the temporality and spatiality of musical canon, Ragamala paintings and Bhakti compositions constitute a spatio-temporal area.

Table 3. Table Showing the Temporal and Spatial Details of Ragamala Paintings of Ragini Bhairavi

| No | Time | Place | Style/Remarks |

| 1 | 1610-29 | Amber | Rajasthani, Western India |

| 2 | 1640-50 | Mandi | North India |

| 3 | – | Bikaner | Rajput |

| 4 | 1765-80 | Bundeli | North India |

| 5 | 1755 | Wanaparti | Dekhani |

| 6 | 1800 | Jaipur | Western India |

| 7 | 18th cent. | Jaipur | Western India |

| 8 | 18th cent. | – | Mughal |

| 9 | 17th cent. | Mughal, Dekhani | |

| 10 | 1770-80 | Murshidabad | Mughal (?), Eastern India |

| 11 | 1760 | Murshidabad | Mughal, Eastern India |

| 12 | 1800 | Amber | Rajasthani, Western India |

| 13 | 1760 | Hyderabad | Dekhani |

| 14 | 1760 | Hyderabad | Dekhani |

| 15 | 1725 | Bilaspur | Eastern India |

| 16 | 1725 | Hyderabad | Dekhani (?), Deccan |

| 17 | 18th cent. | – | |

| 18 | 1760 | Mirpura | Jaikishan (painter), North India |

| 19 | 1760 | Mewar | Western India |

| 20 | 1765-80 | Bundi | Western India |

| 21 | 1725-50 | Malwa | Western India |

| 22 | 1725 | Sirohi | Rajasthani, Western India |

| 23 | 1770 | – | |

| 24 | 1625 | Bhaktpur | Nepal, North India |

| 25 | 1640 | Rajput | |

| 26 | – | Kishangarh | Rajput, Western India |

| 27 | 1680 | Malwa | Western India |

| 28 | 1600-25 | – | – |

| 29 | 1721 | – | – |

| 30 | 1650 | – | Muhammad (painter) |

| 31 | 1520-40 | Mewar | Western India |

Table 4 makes use of the data in Table 2 and 3 and provides an overall view of the frequency and the temporal distribution of canonical texts on music, Ragini Bhairavi, existence of Ragamala paintings and Bhakti compositions. We can also notice that not only the frequency of canonical texts on music increases radically during the post 15th century period, but also the Ragamala paintings. The languages of Bhakti composition suggest the spatiality of these activities. The bold letters in the bottom four rows of the table suggest three different isoglosses, the canonical texts on music, Ragamala paintings and Bhakti compositions, bundling together to produce a cultural area of Bhakti. However, we need to be careful in understanding this particular formulation of Bhakti here. This is not the text-centered, language-specific Bhakti that we have been discussing in literary studies. This is a Bhakti at popular and folk levels on the one hand and music and performance centered on the other that transcends both textual and linguistic constraints. It is a well-known fact that Bhakti compositions have moved across linguistic boundaries and have become trans-linguistic representations. The sectarian plurality and spatial range of compositions in Guru Granth and the itinerary of performing folk theatre across linguistic regions is a strong case to look at Bhakti, Ragamala paintings and music as intermedial representations rather that fragmenting them as textual, visual, and musical representations.

Table 4. Table Showing the Number of Canonical Texts on Music, Number of Bhairavi Ragamala Paintings and Bhakti Compositions on a Temporal Scale in Indian Literatures

| Time | Musical Canon (No = 57) | Ragini Bhairavi’s Paintings (No = 31) | Presence / Absence of Ragamala Paintings | Bhakti Compositions |

| 6th–11th cent. | 4 | – | – | Tamil |

| 12th cent. | 6 | – | – | Kannada Telugu |

| 13th cent. | 5 | – | – | Marathi |

| 14th cent. | 5 | – | + | Assamese Malayalam |

| 15th cent. | 3 | – | + | Dekhani Gujarati Hindi (Braj) Oriya Bengali |

| 16th cent. | 8 | 1 | + | Punjabi |

| 17th cent. | 14 | 10 | + | – |

| 18th cent. | 12 | 20 | + | – |

5. Discussion

The discussions on formalistic and social epistemologies of intermediality, Ragamala paintings and Bhakti compositions bring two important issues to the forefront. The first one is the relationship between text, music and painting, and the second one is their spatiality. Music is formalistically connected with metrical and linguistic structures, including the syllabic structure rules and suprasegmental features of a language. The social epistemology of music is associated with specific families, castes and communities who have a monopolistic control over those knowledge system and the ecological and temporal aspects of singing and performing. While textuality remains relatively static and continuous, musicality and performativity are continually evolving and creative aspects of intermediality. Interestingly, Ragamala paintings, despite belonging to the domain of the visual, have music at the centre. Not only does the term Raga signify music but also there are attempts to visualise emotions associated with music through colours and painting.

Historically speaking, it is during the 13th to 18th century C.E. that a variety of musical genres and canonical texts appeared in medieval Indian literary culture. This is also the time when Ragamala paintings came into existence. In this context, there is a need to study Bhakti in medieval Indian literatures from the perspective of intermediality and as a performance of the popular public sphere. The discussion here is to suggest that it is within the background of such a fusion of polyphonic cultural traditions and a dense archive that we need to understand the intermediality of medieval Indian literary culture.

An earlier version of the paper was presented as the keynote address at National Seminar on Intermediality: From Text to Visual and Visual to Text in the School of Translation Studies and Training, IGNOU, New Delhi on March 1–2, 2016. The author fondly remembers Professor Avadhesh Kumar Singh for the invitation. His academic leadership, profound scholarship and warm friendship are something that I am going to cherish forever. I also wish to acknowledge Professor Subha Chakraborty Dasgupta for going through the paper and providing insightful comments and suggestions.

Notes

[1]In many Indian languages, the term for folk theatre subsumes openness or street within the term: Terukuttu (street theatre, Tamil), Vithi-natakamu (street theatre, Telugu), Shreni–natak (street theatre, Gujarati), Nukkad (street corner theatre, Hindi).

[2]For a detailed discussion on this issue, see Satyanath (2010, 2021).

[3]For a detailed discussion see, Satyanath (2009) and Rao.

[4]That of Hindustani style of music and Melakarta Raga of Karnataki style of music could be roughly referred as the Heptatonic scale of Western music.

[5]The figure is from Abhijit Bhaduri’s blog. (Source: https://scontent-del1-1.xx.fbcdn.net/v/t1.6435-9/82950522_2801404213416888_3717761719058038784_n.jpg?stp=dst-jpg_p526x296&_nc_cat=105&ccb=1-7&_nc_sid=730e14&_nc_ohc=iNaCnfUf7-kAX-Fc-dV&_nc_ht=scontent-del1-1.xx&oh=00_AfAdDQRd0Ov8LnIweuA3OGZAB5jhCG5fZgk2xMOlQywCmg&oe=6533B04B), accessed on 30th March, 2023.

[6]The Ragamala paintings usually follow the schema proposed by Mesakarna or Kshemakarna, a rhetorician from Rewa in central India. In his treatise Ragamala, written in Sanskrit in 1570 C.E., he outlines an elaborate system of six Ragas, each having five Raginis and eight Raga-putras, except for Raga Shri, which has six Raginis and nine Raga–putras. Put together, the schema of Mesakarna creates a Ragamala family consisting of six male Ragas, thirty-one female Raginis and forty-nine Raga–putras, resulting in a total of eighty-six Ragas. Apart from this, there is another schema called the Hanuman Mata that stipulates five wives for each of the male Raga. The numbers of Ragas and their names and the time at which they are to be sung is not consistent and vary from text to text.

[7]https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/image/35864001, accessed on 10th October, 2020.

[8]Some of these details are strikingly uniform with regard to several paintings of Ragini Bhairavi.

[9]My sincere acknowledgements are due to Professor J. Srinivasamurthy, former professor of Sanskrit, M.E.S. College, Bangalore for reading the Sanskrit verse and providing its meaning.

[10]The reference to Narada here could be to a canonical text on music, Sangita Makaranda, which could have been composed sometime between 7th–11th centuries C.E. It is in this text that the earliest reference to the concept of the family of Ragas, Raga–parivara appears.

https://vmis.in/upload/Assets/Exhibition/23/ragmala/Part2.html, accessed on 10th October, 2020.

[11] Raja Sawai Venkata Reddy ruled Wanaparthy Samshtanam during 1746–63 C.E.

[12]Jagati is a Vedic meter of four lines with twelve syllables in each line. Acknowledgements are due to Professor J. Srinivasamurthy and Professor S. Shesha Shastry, former professor at Sri Krishnadevaraya University, Ananthapur for reading the verse.

[13]Doha is a couplet, with twenty-four Matras in each line with the last word of the lines having an end rhyme.

Chandra (92) provides the description of the painting as follows: “The heroine is dressed in usual Rajput garments, with an Arati (torch light) in her left hand and a bell in the right, is worshiping the Shiva Lingam. Behind her, two female musicians are playing on Mridanga and cymbals respectively. In the background, three trees are swaying in the wind. In the foreground is depicted a lake full of lotus buds.”

[14] Chaupai is a four-line verse, each line having sixteen Matras.

Chandra (93) describes the painting as follows: “In this picture a temple of Lord Shiva situated on the banks of a lake full of lotus blossoms and sporting ducks is depicted. The heroine is seated in the temple before the Shiva Lingam with some offerings in her hand. In front of her various requisites of Puja such as bell, casket, Arghya (water meant for offering), Panchapatra (vessel that contains water to be offered during worship), etc. are to be seen. Four handmaids with various articles for offering stand outside the temple. Lotus flowers seem to have been the chief decorative motif of the painter. They are growing in abundance in the lake, the heroine’s skirt has lotus patterns and even the Lingam is decorated with them.” The meaning given within brackets is by the author.

[15]Savaiya is a four-line verse with twenty-two to twenty-six syllables in each line with the last word of the lines having an end rhyme.

Chandra (96) description of the painting is as follows: “The heroine wearing a Mukata (headgear), a white Orhani (upper garment) and the usual ornaments is seated on the right, in a temple of Shiva situated in the midst of a lake full of lotus blossoms. A handmaid, dresses in a Mukata and yellow Orhani stands on the other end.” The meaning given with in brackets is by the author.

[16]While Deshkar is a morning Raga sung during time slot that Bhairavi is sung, Bhop is an evening Raga. However, scholars also point out the similarities between the two.

[17]The lyrics given here is from https://www.aathavanitligani.com/Song/Priye_Paha_Ratricha_Samay

and the translation is from https://veerites.worldpress.com/2017/05/23/priye-paha-translated-into-english-23-5-17/.

The musical rendering of the song Priye-paha sung by Prabhakar Karekar could be accessed here:https://sonichits-com/video/Pt._Prabhakar_Karekar/Priye_paha.

The sites were accessed on 30th March 2023.

[18]https://youtu.be/GSEjL-FpSbo?t=21, accessed on 30th March 2023.

References

Bakhtin, M.M. The Dialogic Imagination. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1981.

Chandra, Moti. “Studies in Indian Dancing as depicted in Painting and Sculpture and the Representations of the Musical Ragas in the Paintings.” Ph.D. Thesis, University of London, 1934.

Ebeling, Klaus. Ragamala Painting. New York: Adam Center, 1972.

Jakobson, Roman. “On Linguistic Aspects of Translation.” 1959. The Translation Studies Reader, ed. by Lawrence Venuti, pp. 113–118. New York: Routledge, 2000.

Kattenbelt, C. “Intermediality in Theatre and Performance: Definitions, Perceptions and Medial Relationships.” Culture, Language and Representation, 4 (2006). 19–29.

Kristeva, Julia. Revolution in Poetic Language. New York: Columbia University Press, 1974.

Nijenhuis, Emmie te. Musicological Literature. Wiesbaden: Harrossowitz, 1977.

Ramanujan, A.K. “Three Hundred Ramayanas: Five Examples and Three Thoughts on Translation.” In Paula Richman edited, Many Ramayanas: The Diversity of a Narrative Tradition in South Asia, pp. 22–48, Berkeley: University of California Press, 1991.

Patil, Chennabasappa. “Panchatantra Sculptures and Literary Traditions in India and Indonesia: A Comparative Study.” In Marijke J. Klokke edited, Narrative Sculpture and Literary Traditions in South and Southeast Asia, pp. 73–95. Leiden: Brill, 2000.

Rao, M.S. Nagaraja. Kiratarjuniyam in Indian Art (With Special Reference to Karnataka). Delhi: Agam Kala Publications, 1979.

Rejewsky, Irina O. “Intermediality, Intertextuality and Remediation: A Literary Perspective on Intermediality.” Intermédialités: Histoire et théorie des arts, des lettres et des techniques, 6 (2005). 43–64.

Satyanath, T.S. “Tellings and Renderings in Medieval Karnataka: The Episode of Kirata Shiva and Arjuna.” In Judy Wakabayashi and Rita Kothari edited, Decentering Translation: India and Beyond, pp. 43–56. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, 2009.

Satyanath, T.S. Kavya as Knowledge Systems. Kolkata: Department of Comparative Literature, Jadavpur University, 2010.

Satyanath, T.S. “Towards Comparing Indian Writing Culture.” In Dilip Borah edited, From ‘Vishwa’ to ‘Bharatiya’: New Essays on Comparative Indian Literature, pp. 62–82. Delhi: DVS Publishers, 2021.

Wolf, Werner. “Intermediality.” In David Herman, Manfred Jahn and Marie-Laure Ryan edited, The Routledge Encyclopaedia of Narrative Theory, pp. 252–256. London: Routledge, 2005.

Wolf, Werner. (Inter)mediality and the Study of Literature. CLC Web: Comparative Literature and Culture, 13.3 (2011). http://dx.doi.org/10.7771/1481-4374.1789, accessed on 30th March, 2023.

Zebrowski, Mark. Deccani Painting. New Delhi: Roli Books International, 1983.

Download PDF